Pioneer Russian Postcards

Art postcards of the late 19th - early 20th century

A. Yartseva

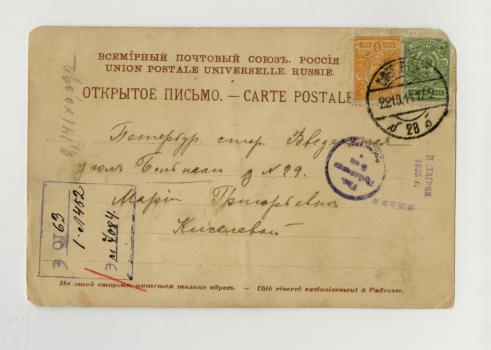

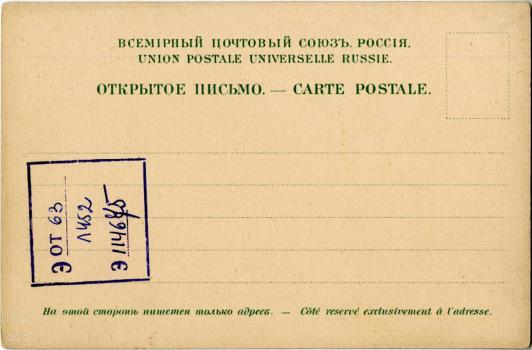

As a new means of communication, mailing cards was introduced to Russia in 1871. For the next two decades, postal cards were produced and distributed by the government. One side of postcards was for a message, the other side was exclusively for the delivery address. No message was permitted on the address side of postcards; otherwise, they were not accepted by the Post Office according to postal regulations.

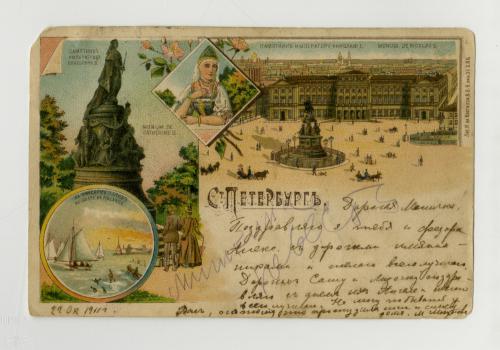

In 1894, private publishers were allowed to issue postcards. Soon the first Russian picture postcards appeared. The back of the picture postcard was still exclusively for the address, stamp and postmarks. Images could be printed only on the message (front) side. If the card had an image, then a small space was left on the front for a message. Often people had to write messages across the card’s image, but sometimes cards were produced with pictures small enough to leave space for written messages to be added.

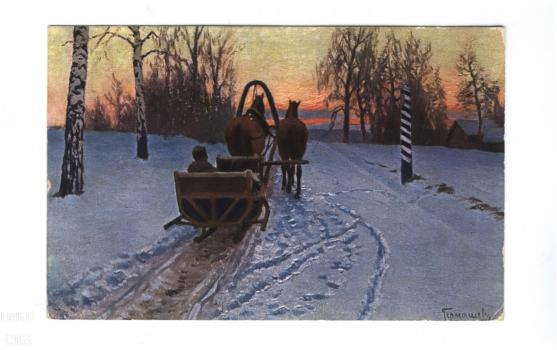

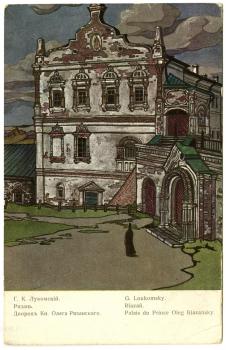

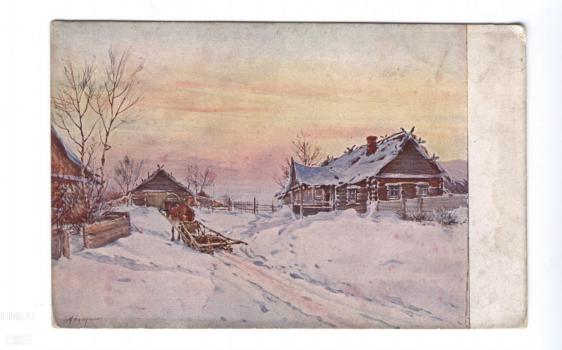

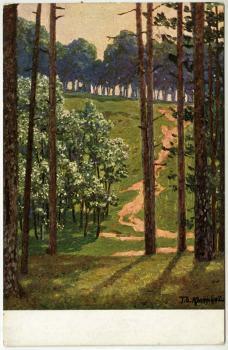

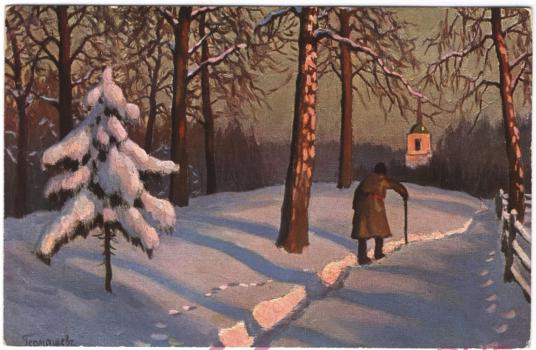

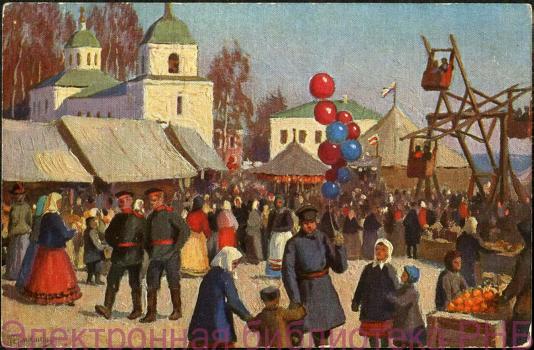

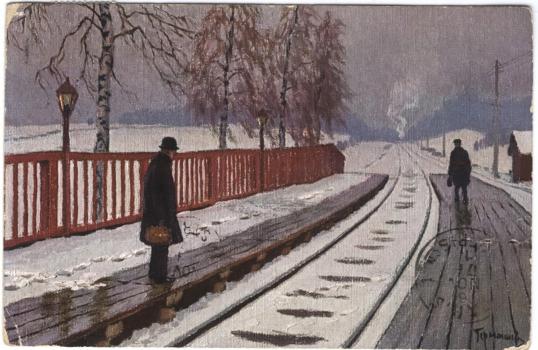

Already at the end of the 19th century, art postcards began to be produced along with photo postcards which beared a photographic image. Art cards were reprodutions of both existing pieces of art and works specially designed to be placed on postcards.

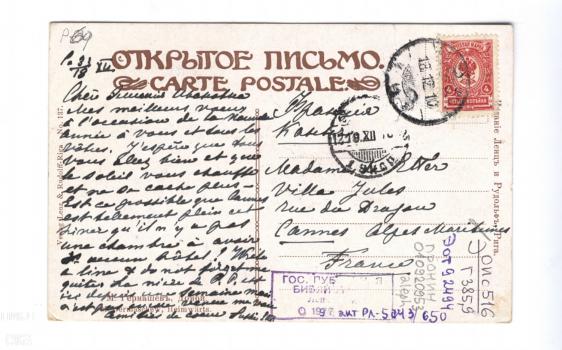

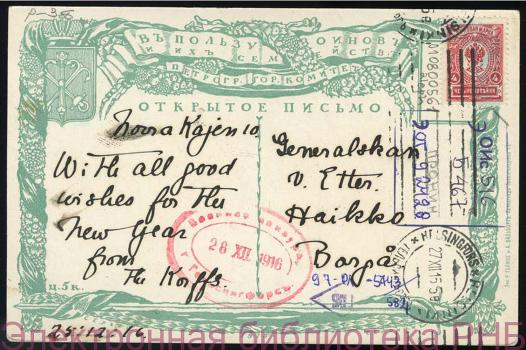

In 1904, a considerable change on the address side of postcards occurred. Postcard backs were divided by a line in the half — the right side was for the address, the left for a written message. This allowed an image to take up the entire front of a card.

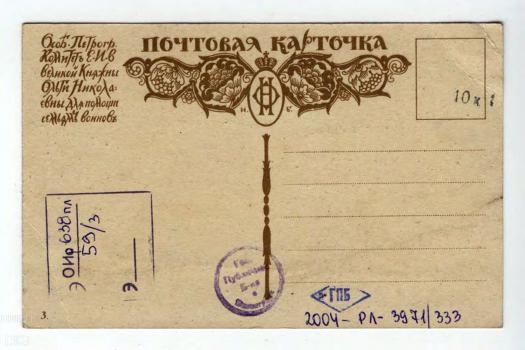

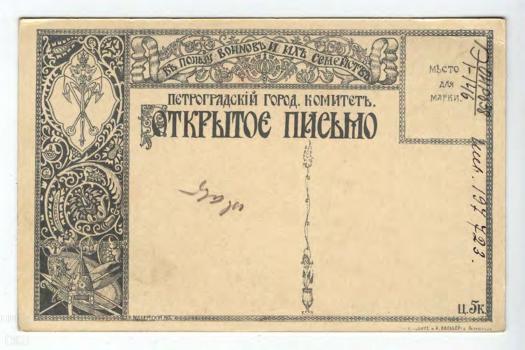

The postcard developed in Russia during blossoming applied graphics, when theater programs and invitation cards, book and magazine illustrations were created by outstanding artists. Their designs of the address side of postcards constitute another facet of the art of the Silver Age. Based on design requirements, a number of well-known talented artists turned the address side into a masterpiece of graphic art: such are the drawings by Ivan Bilibin, Sergei Chekhonin, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky and other authors.

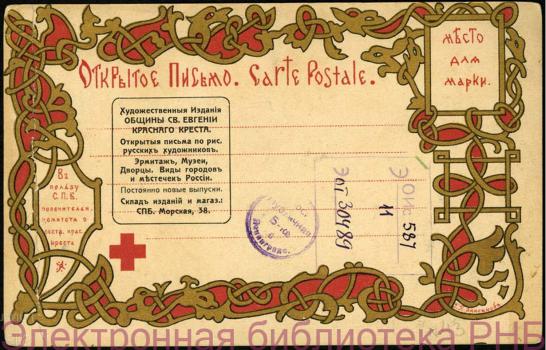

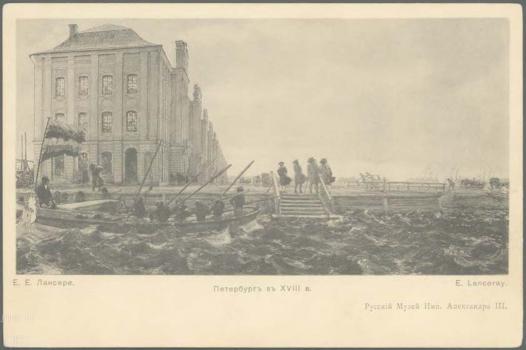

In 1898, the Community of St. Eugenia started printing postcards in St. Petersburg. They became a major national postcard publisher, producing more than 6,000 card titles over the next two decades.The publisher employed many celebrated artists from the World of Art group to create images for them and carefully select artworks for reproductions. The postcards of the Community of St. Eugenia are characterized by a broad range of subjects and the highest quality of printing. Thanks to all this, these cards are rightfully considered one of the best. The publisher used more than 15 variations of a design to print the address side of postcards. The most famous was made by Evgeny Lansere Lanceray and was applied for ten years, from 1904 to 1914.

In 1904-1906, the Board of Trustees of the Community of St. Eugenia published the Postcard magazine. It was subtitled The Illustrated Chronicle of Postcards, and its aim was to promote "highly artistic postcards". This was Russia's first postcard dedicated magazine. The magazine consists of articles about artists who created postcards and postcard history. It also gave advice to collectors. Two supplemental Albums of Autographs and Author's Drawings were also issued to celebrate New Year and Easter. As a special addition to the periodical, subscribers received about 20 postcards, two of them were based on drawings by the magazine's editor, artist Fyodor Berenstam.

There were other postcard publishing companies along with the Community of Saint Eugenia. In the same 1898, a series of view-cards after watercolors by Nikolai Karazin, depicting St. Petersburg, was issed by the St. Petersburg merchant Otto Kirchner, the owner of a factory of account books. In 1901, the Moscow antiquary and print seller Alfons Felten reproduced drawings by the then popular author Sergei Solomko on postcards. They were made in the etching technique, rarely used for postcards.

Sometimes postcards were published for charitable purposes. In this case, they were printed using a number of societies that provided assistance to the poor or students of various educational institutions. For example, the Luban Society for Assistance to the Poor received so much of its annual income from the sale of postcards as they did from membership dues. The organization planned to issue after 1915 up to ten series of postcards, each consisting of my ten thousand copies. The design of the address side for the Society's postcards was made by Georgy Narbut.

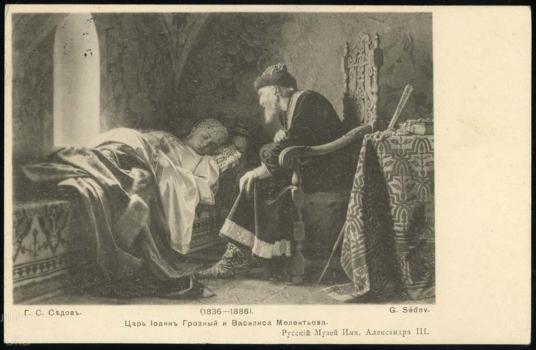

Many of the early 20th century postcards were reproductions of museum paintings or contemporary works. For example, such a big publisher like the Kiev Rassvet acquired the exclusive right to publish paintings and sepia by a famous artist, academician Wilhelm Kotarbinsky. The Imperial Women's Patriotic Society released series of postcards dedicated to the Hermitage and the Russian Museum in 1902-1903. Along with a charitable task, these postcards introduced the classics of art to the general public. Postcards were published by the painters themselves (for instance, by the artists A.V. Makovsky and A.I. Lazhechnikov), and by museums. For instance, hundreds of postcards were issued by the Russian Museum of His Imperial Majesty Alexander III between 1910 and 1917. The cards, along with reproductions and cheap illustrated catalogues, brought income to the museum, allowing non-profit scientific and artistic works to be published. On the first postcards by the Russian Museum, the address side was designed by Iosif Charlemagne, then a drawing by Georgy Narbut was used.

Many companies published multi-color postcards, reproducing paintings by Russian and foreign masters, as well as drawings created specifically for postcards. The founder of the Richard publishing company was a St. Petersburg merchant of German origin Richard Lutherman Jr. In the 1890s, Lutherman had a warehouse and a workshop of artificial flowers, greenery and accessories for them in St. Petersburg. In the 1900s, he also became an owner of a paper goods warehouse, which later turned into a stationery store. Color art postcards by the Richard company began to appear no later than 1906. They were printed most often in the printing house of the R. Golike and A. Vilborg Partnership. The history of the publishing house ended during the First World War, when Lutherman was expelled from Russia as a German national.

The Lenz & Rudolff company was founded in 1900 in Riga. They not only sold books, representing a number of German publishing houses in the Russian Empire, but also published colour art and black & white picture postcards.

In 1908, the native of the Russian Empire Ilya Lapin set up the Ilya Lapiná & Co partnership in Paris. From 1913, this company became known as "Ilya Lapiná" - this is how Ilya Lapin changed his surname in the French manner. Starting from the last years of the 19th century, Lapin lived in the French capital, and at the 1900 Paris Exposition, he exhibited prints of watercolors and drawings in the Russian pavilion. His publishing house is famous for albums (for the centenary of Russia's victory over the French invasion of 1812, for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty and others) as well as reproductions and postcards. The printer and fine art publisher produced high quality postcards that featured paintings by various artists. In 1914, Lapin was awarded the title of Knight of the Legion of Honour for services to French industry and art.

From the mid-1880s, Carl Gustav Granberg worked in the Swedish capital in a publishing company which by 1896 had passed into his possession. The Granberg Joint Stock Company was set up in Stockholm to produce color art, souvenir and view cards. Until the outbreak of the First World War, they were distributed mainly in Russia. Granberg repeatedly visited Russia and, expanding his business, increased the production of postcards for our country. With the death of Granberg in 1923, the firm ceased to exist.

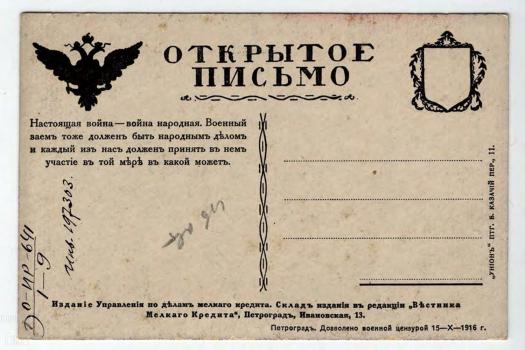

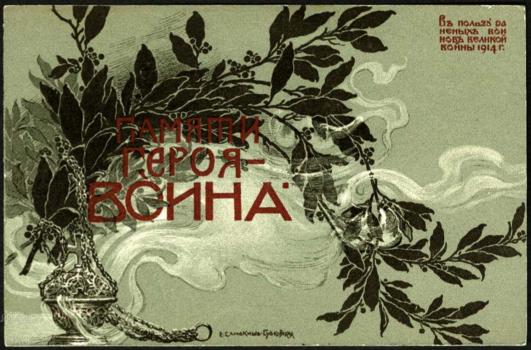

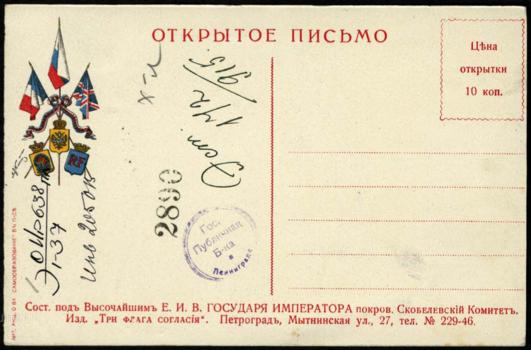

Postcards issued during World War I featured other themes. In particular, caricature postcards became widespread - they ridiculed Russia's enemies in the war. New publishing houses were also established. Postcards were issued by committees to assist soldiers and their families, refugees and all the people affected by the conflict.

One of the old charities, the Imperial Philanthropic Society established a special fund to maintain mobile hospitals and shelters. On October 15, 1914, it had an one-day fundraiser that collected 32 thousand rubles to a donation box "through the sale of patriotic postcard after a drawing by D. Sharapov. The postcards by the Small Loan Department repeated the well-known poster series dedicated to the 5 ½% war loan.

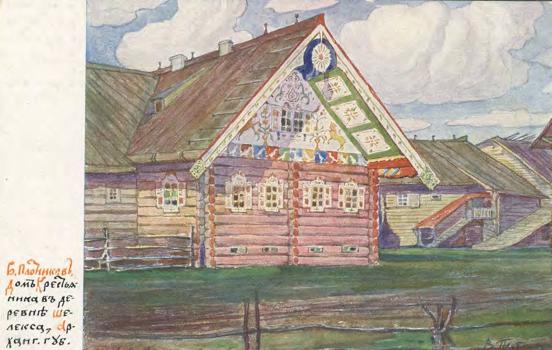

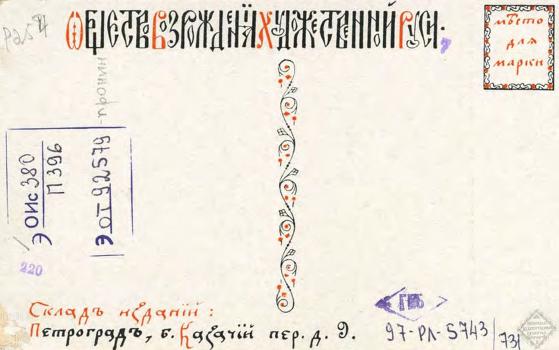

The war years saw a rapid rise in the national spirit and an increasing interest in the history of national culture. Evidence of this can be seen in Russian postcards. In 1915, the Society for the Revival of Artistic Russia was founded to spread knowledge of Old Russian art, in all its forms, among the Russian people and to advance it in the modern conditions. They used postcards to "introduce Old Russian art samples into the minds of the common people".

Undoubted attention to the origins of national art is noticeable in the expressive works by Dmitry Moor. His illustrations for a fairy tale by Alexei Remizov, published in 1917 in the Creativity almanac, were also issued as postcards. Old Russian icon paintings and manuscript miniatures inspired a series of postcards designed by Boris Zworykin and published in 1916 in Moscow by Alexei Postnov.

For a quarter of a century of its existence, art postcards found an important place in everyday life in pre-revolutionary Russia. They were sold both per piece and in series (in this case, discounts could be expected). The cheapest cards cost 1 kopeck, postcards of a higher quality were sold for 510 kopecks. Postcards were very profitable goods for those who produced or sold them.

A 1915 advertisement exclaimed, “If you have not yet practiced selling artistic postcards in your store, then do not miss this favorable moment to try out this branch of making money. With minimum expenses and risks for you, it will more than cover the costs shortly, and now is the best time to sell postcards".

Since the end of the 19th century postcards have become an object of collecting. Collectors gave, for example, such announcements: “Exchange colored postcards. I will send them in exchange for any couples in love and all views of the Urals and Perm".

Two thematic collections assembled over the first three decades of the 20th century by I. Churakov and N. Alekseev, continue to be preserved in the National Library of Russia. Together with the so-called Main Collection, they constitute significant holdings of postcards, cared for by the Prints Department of the National Library of Russia. They illustrate the history of postcards from modest forms, which bear only a stamp, to multi-color printed artworks.

![Ostroumova-Lebedeva A.P. St. Petersburg: [Admiralty Visible through the Branches of Trees] Ostroumova-Lebedeva A.P. St. Petersburg: [Admiralty Visible through the Branches of Trees]](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA5524/MA50709/s_NA55387.jpg)

![Maksimov A.F. [In the line of fire] Maksimov A.F. [In the line of fire]](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA5524/MA51317/s_NA56012.jpg)

![Samokish N.S. [Mail] Samokish N.S. [Mail]](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA5524/MA50864/s_NA55535.jpg)