Winter-in-St.-Petersburg-City Postcards

-

Picture cards by Otto Kirchner, Granberg, Ernst G. Svanström, Iliay Sepheriades, Richard

-

Postcards Printed by the Community of St. Eugenia

Postcards Printed by the Community of St. Eugenia

Images by Albert Benois was also used by other postcard publishes, including the Community of St. Eugenia, a publishing house and a subsection of the St. Petersburg Committee of the Red Cross. This publishing company became the largest producer of postcards in Russia. They manufactured a great many finely printed postcards. The Community issued twenty picture cards based on Benois's originals. The same square of the St. Nicholas Naval Cathedral was shown on paired cards issued in 1903: one depicted it in winter, the other in summer. The postcards were produced by an innovation color-printing method called chromolithography by Alexey Ilyin’s Cartographic Establishment which was famous for high quality products.

More than a decade later, in 1915, a watercolor painting by Albert Benois, depicting the winter city, was reproduced on a postcard Petrograd. Anichkov Palace by the Moscow Anatoly Mamontov Printing House. The printer sometimes partnered with the publishing house of the Community of St. Eugenia. You get a nice view of the Anichkov Palace where the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna lived then. The artist show a clear frosty day, Nevsky Prospekt in front of the palace is almost empty. It's hard to imagine, but in less than two years, the crowd will burn the symbols of imperial power in the same place (this scene will remain on a postcard from the time of the February Revolution of 1917).

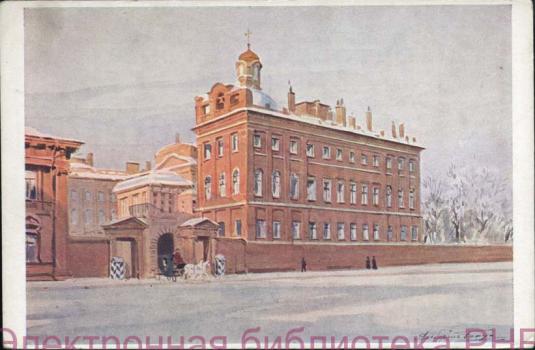

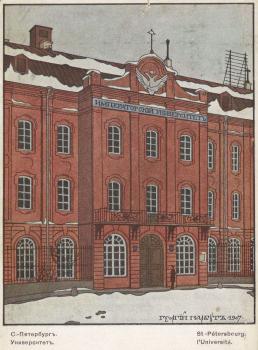

The end of 1902 saw the birth of a creative alliance between the publishing house of the Community of St. Eugenia and the World of Art Association. The special subject for members of the World of Art group was Saint Petersburg. In the early 20th century, the leader of the association Alexander Benois wrote, “We <...> will not tire of repeating that St. Petersburg is an amazingly beautiful city, the likes of which are rare in the world»4 It is clear that St. Petersburg's winter views are often found on postcards by the St. Eugenia Community, based on the World of Art's works. Georgy Narbut (1886‑1920) lived a very short life, but managed to go down in the history of Russian and Ukrainian art. This outstanding master of graphics joined the World of Art in 1910, but even earlier his work was strongly influenced by Ivan Bilibin, a famous member of the group. Arrived in the capital from the Ukrainian city of Glukhov in 1906, Narbut began to study at the Faculty of Philology of St. Petersburg University. At the same time, he enthusiastically practised the fine arts. A postcard St. Petersburg. University by the St. Eugenia Community cannot but remind us of the university period of his life, which lasted a year. The card was printed in September 1908, but was drawn in 1907. Out of ten Narbut's postcards created for the St. Eugenia Community, only it depicts St. Petersburg architecture - the former building of the Twelve Collegia, built in the first half of the 18th century.Mstislav Dobuzhinsky (1875-1957), a graphic and theater artist, illustrator, became a member of the World of Art group in 1902. In December of the same year, he was invited to design several original works to be placed on postcards bythe publishing house of the Community of St. Eugenia. Thanks to this, M. Dobuzhinsky, in his own words,“set to work on Petersburg themes“5. The first artist's postcards include Alexandrinsky Theatre: the strict harmony of the architectural complex built in the Empire style is combined in the picture with white snow covering Alexandrinsky Square and Nevsky Prospekt. This work is a clear evidence that M. Dobuzhinsky loved “stern, elegant views” of the city in which he lived from the age of eleven, and admired “magnificence and harmony of its wonderful architecture”6. However, in the early 20th century, as Dobuzhinsky wrote,“I began to see not only this unique beauty of St. Petersburg – It seems I was touched even more by the backside of the city, its “shadows”7. This side is revealed on the postcard Chernyshev Bridge (now Lomonosov Bridge), published in 1903. The card shows contrasts of the city: among beautiful buildings you can see “curious fish cages“8 in the Fontanka River.

(галерея-MA45473)

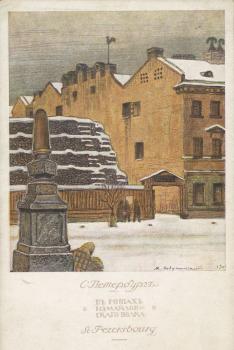

In the 1900s, M. Dobuzhinsky and his wife lived in a district familiar to the artist from childhood, at first – in the 6th Сompany of the Izmailovsky Regiment, then in the 7th Company (now 6th and 7th Krasnoarmeisky streets). The streets were named after the Izmailovsky Regiment which was once quartered nearby. As the artist wrote, “the surroundings of our dwelling were gloomy”9. A postcard from 1905, which reproduces a 1904 watercolour painting kept in the Russian Museum, features “an old milestone in the form of an obelisk, which brought a special note to this landscape and weakly, but gave consolation”10. The milestone dating 1770s, made of granite and marble, is now a historical landmark of federal importance. It is located on the corner of 7th Krasnoarmeyskaya street and Moskovsky Prospekt11 (former Zabalkansky Prospekt which Dobuzhinsky described as “one of the most ugly and even scary streets”12.

In the postcard Izmailovsky Prospekt, against a background of the architectural scenery of the early twentieth century, a remarkable meeting of two forms of urban transport took place: two horsecars with an electric tram. The passenger horse-drawn tram appeared in the city in 1863. The city's electric tram line which was laid from the Technological Institute to the Baltic Station and passed along Izmailovsky Prospekt was launched in September 1908. In December 1906, when the postcard was printed, the route operated in Saint Petersburg for a year. In the background, there is a regimental church of the Life Guards of the Izmailovsky Regiment, which M.V. Dobuzhinsky “knew and loved since childhood” 13 and the memory of “the majestic white Trinity Cathedral, with five blue domes with large gold stars”14 remained with him always.

Dobuzhinsky highly appreciated the efforts of the Community of St. Eugenia and stated, “It seems that my and Ostroumova's numerous citiscapes15, since 1903 printed on very popular and widely spread in Russia cards by the Red Cross, played a significant role in promoting the city of St. Petersburg”. Views of St. Petersburg and its suburbs became a popular subject for Anna Ostroumova‑Lebedeva (1871‑1955), a famous graphic artist and a member of the World of Art group since 1899.

“I'm not willing to describe our city that is so unlike any other in the world. I just don't dare. After Pushkin, who can describe this austere, majestic, and fasinating city more inspiringly and profoundly”16, the artist asserted. Her favorite places include “the Old Stock Exchange with paired Rostral Columns, the embankment near it with beautiful granite descents. They end with two huge balls. 17.

By December 15, 1901, Ostroumova-Lebedeva had to complete her work of which she wrote in a letter to a friend, “I had to draw at sixteen degrees below zero. ... I think I will get an interesting engraving”18. It was published in a monthly journal called Artistic Treasures of Russia (1902, No. 1) and preceded the article by Alexander Benois about the statue of a river deity placed at the foot of the Rostral Column. In 1909, Ostroumova-Lebedeva engraved a postcard-sized replica of this work for the publishing house of the Community of St. Eugenia. The artist showed this engraving, among others, at the 7th exhibition of the Union of Russian Artists: in Moscow (1909-1910), in St. Petersburg (1910)19 and, very likely, in Kiev (1910)20. In March 1910, the postcard Rostral Column in Snow was printed by the R. Golike and A.Vilborg Partnership, using two woodcut boards. The above-mentioned Moscow exposition of the Union of Russian Artists introduced some Ostroumova‑Lebedeva's watercolor paintings to the audience for the first time. The artist initially practiced watercolors as preparatory drawings for engravings. But according to her, “I wanted to master the art of watercolor so that I could easily and freely create works of considerable artistic value. <...> Advancing techniques, I ruthlessly destroyed my works without showing them to anyone <...>. And only when I felt that I had made picturesque watercolors, I gave them to the exhibition. They had success”21. Among them was the work At the Stock Exchange. The snow-covered descent at the Rostral columns and snowbound Neva ice were depicted by Ostroumova-Lebedeva in accordance with her preferences: she was “interested in pure watercolor painting, without using whitewash, where paper plays the role of whitewash”22. And although you can note signs of winter in this work, they were most likely seen already in the first days of spring 23.Postcards reproducing watercolors were received by the publishing house of the Community of St. Eugenia from the printing house at the end of November 1909, and the original was purchased by a private person at the St. Petersburg exhibition of the Union of Russian Artists in 1910. A few years later, in 1912, the artist uses the same image in black-and-white woodcuts – a headpiece to the section Vasilyevsky Island of the art-historical essay by V.–Kurbatov Petersburg24.

In Russian poetry of the Silver Age, there are not so many references to winter in the capital of the Russian Empire, “yellow steam of the St. Petersburg winter, yellow snow sticking to the slabs” (I.F. Annensky), “oh, mysterious winter days” (A.A. Akhmatova ), “I love this city, quite unprotected from winter snowstorms ” (M.A. Voloshin), “Snowy St. Petersburg twilight” (A.A. Blok). That's how a guidebook dated the late 1910s described this season, “since its founding, the northern capital has been known for very unhealthy, wet, unfriendly and variable weather. The city that is close to the sea is influenced by a maritime climate <...> with milder winters than in inland areas at the same latitude. <...> The coldest month is January at -9.1°C, then December at -8.1°C, February at -7.3°C<...>. Thus, the Neva is covered with ice for about 4-5 months, providing navigation for a little more than 200 days of a year. Spring in Petrograd usually starts late, and it often snows in April (and occasionally in May)”25.

Words of the important Russian artist Alexander Benois come to mind when looking at twenty-two postcards drawn from our collections for the exhibition. In the 1930s, far away from St. Petersburg, he recalled his children's notions about the winter time. Benois remembered that winter in the city was a real challenge, “In St. Petersburg, it was not only cold and snowing, but something gloomy, dangerously freezing, frightening was coming. And there was something invigorating in the fact that all these horrible things were nevertheless completely overcome, that people were smarter than the nature's power. It was during the deadly winter season that Petersburgers indulged in fun and merriment with particular zeal. <...> In St. Petersburg, the winter was harsh and terrible, but in St. Petersburg, people learned, as nowhere else, to turn it into something pleasant and magnificent ”26.

A. V. Yartseva

![Benois A.N. [ St. Nicholas Naval Cathedral Square in Winter (Spb.)] : postcard Benois A.N. [ St. Nicholas Naval Cathedral Square in Winter (Spb.)] : postcard](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA5185/MA46666/s_NA51156.jpg)

![Ostroumova‑Lebedeva A.P. Rostral Column in Snow : [Saint‑Petersburg] : postcard. Ostroumova‑Lebedeva A.P. Rostral Column in Snow : [Saint‑Petersburg] : postcard.](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA5185/s_NA51567.jpg)

![Ostroumova‑Lebedeva A.P. At the Stock Exchange : [Saint‑Petersburg] : postcard. Ostroumova‑Lebedeva A.P. At the Stock Exchange : [Saint‑Petersburg] : postcard.](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA5185/s_NA51568.jpg)