"For the knowledge of all the people": engravings of the time of Peter the Great in the collection of the National Library of Russia. Marking the 350th anniversary of Peter I

Grand Embassy

The materials on the Grand Embassy illustrate several important moments and key events at the beginning of the reign of the reformer tsar. Firstly, they indicate Peter the Great's interest in European achievements. Secondly, they vividly demonstrate Peter's practical approach to the art of printmaking and his understanding of its importance. Tthirdly, they immerse the viewer in the stormy atmosphere of the turn of the 17th-18th centuries.

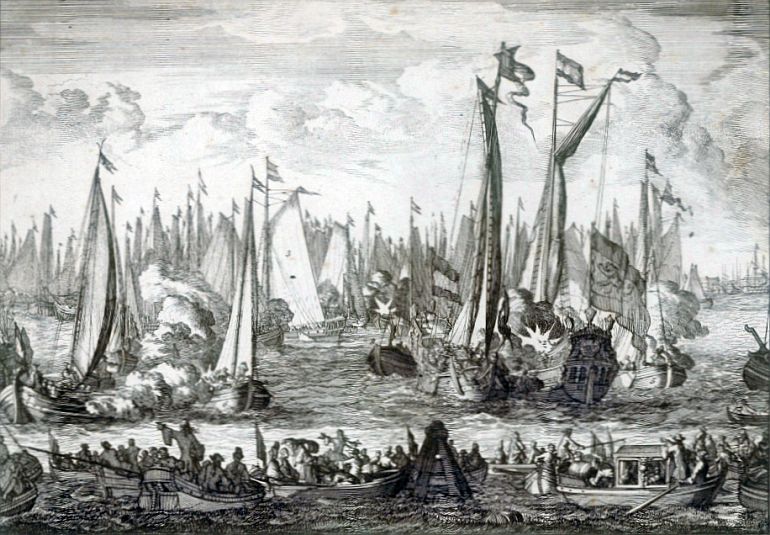

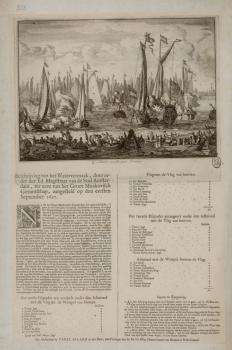

In 1697-1698, the young Tsar Peter traveled around Western Europe, touring some European capitals. He actively acquire innovative scientific and artistic knowledge in the field of fortification, artillery, exact sciences and art. Peter visited European countries incognito, but the embassy was happily greeted everywhere, and the fact of the arrival of Peter Alekseevich was widely known thanks to the then press. Thus, a leaflet,published in Amsterdam, informed readers about "a water entertainment organized by the Magistrate of the city of Amsterdam in honor of the Grand Moscow Embassy" on September 1, 1697. The city celebrated the arrival of Peter with a maritime show in the form of mock battles, with the participation of various vessels.

Thanks to the spectacular and detailed engraving of 1697 by Daniel Marot “The Great Audience Hall Where the Gentlemen of the States General of the United Provinces Receive Envoys in The Hague”, we can see the newly built Travessaal in the Binnenhof Palace, where the States Generals recieved the Grand Embassy. Peter I attended there as an unnamed nobleman.

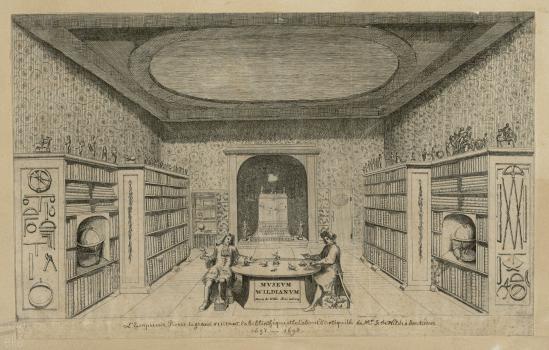

It is interesting that before the trip to Europe, Peter I was already familiar with engravings - European news sheets and reports were translated into Russian even during the reign of Peter's father, Tsar Alexis of Russia. They were published in the first Russian hand-written newspaper News- Kuranty, established at the court. German or Dutch "fly sheets" could reach major Russian cities. It is only logical that the very first and most important Peter's steps in Europe were well documented in engravings. So, in 1697, he visited the famous Jacob van de Wilde Museum in Amsterdam, which was a large private collection of ancient sculpture, paintings, coins, medals, scientific instruments and other things. De Wilde's daughter Maria captured Peter's visit in a drawing that then was used for a engraving.

Peter obviously understood the importance of prints as a “mass media” of the 17th-18th centuries, as a tool for creating a positive image of Russia, a visual representation of its victories and other politically significant events. The first victory of Peter - the capture of the Turkish fortress of Azov, which crowned the Second Azov campaign of 1696 - was depicted by Adrian Schonebeck in an engraving of 1699. The parallel Russian - Latin text was intended to increased the reach of the educated public, and the dynamic baroque style of engraving followed modern trends in fine arts.

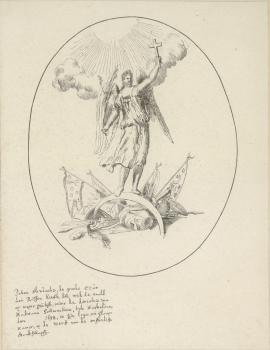

Based on the current state of the world and engraving technique, Peter the Great in Amsterdam made an engraving himself. The Turkish theme was one of the main сoncerns of Europeans for many centuries. It brought together the interests of seemingly so different states as the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation, the Republic of Venice, and Russia. Especially in the context of the Turkish threat, Peter's victory, the capture of Azov in 1696, looked very significantly. It is not surprising that under the guidance of the Dutch master Adrian Schoonebeck, Peter created an engraving depicting an allegory of the triumph of Christianity.