To Be Napoleon Each Wishes

Bonaparte – General of the French Revolutionary Army (1796–1799)

The earliest autographs of Napoleon, housed in the National Library of Russia, date back to the Italian campaign of 1796–1797.On March 2, 1796, a 27-year-old Bonaparte, then little-known general, was appointed commander of the French Army of Italy. Allready on March 27, Bonaparte arrived at the main headquarters in Nice and tried to immediately get straight to the point. Of principal concern was not only the state of the army but also the attitude of the valiant generals Massena, Augereau, La Harpe and others towards the new commander-in-chief. Honored military generals were not enthusiastic about coming under the authority of a young inexperienced commander.

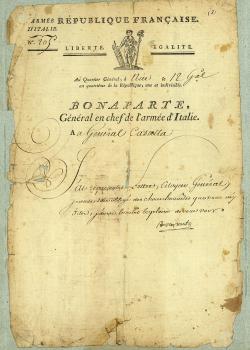

Probably Brigadier General Antoine-Philippe Casalta (1759–1846) was most loyal to Bonaparte. A Corsican by birth, Casalta joined the French Revolutionary Army in 1792, participated in many battles, was wounded more than once. From September 1795, he fought in Italy under Massena. He knew well the situation in the Army of Italy, the mood among the soldiers and commanders. Casalta, apparently, quite correctly assessed the situation in general. A few days after arriving in Nice, on April 1, 1796, Napoleon addresses him with a short note, “I have received your letter, Citizen General, and I am very much indebted to you for your honest opinions. I will soon have the pleasure of meeting you in person. Bonaparte».Many historians consider the Italian campaign of 1796–1797 against Austria and Piedmont to be the most brilliant campaign of Bonaparte's military career. For the first time, Europe learned about Napoleon. French regiments entered Italy on April 9, and three days later the first serious battle was won at Montenotto.

Bonaparte led his army from victory to victory in a series of the battles of Millesimo, Dego, Cheve, Mondovi, forcing Piedmont to sign a separate peace on May 15 in Paris. Austria was left without an ally and soon lost lands that had belonged to it in northern Italy.

The Italian campaign greatly contributed to Napoleon's development as a commander, as well as to the establishment of the French army which gradually grew into a powerful force. At the same time, the army became multinational. In October 1796, Bonaparte formed the Lombard Legion, consisting of Italian patriots and Jacobins. In January 1797, General Dombrowski (1755–1818) signed the agreement marked the creation of the Polish Legions that served with the French Army.

In 1797, the Polish Legions formed a force of 7,000 men who emigrated to Italy and France after the Kosciuszko uprising. Since French laws did not allow the use of foreign troops, Polish military forces joined the army of the Republic of Lombardy ( Cisalpine Republic) under the command of Bonaparte.

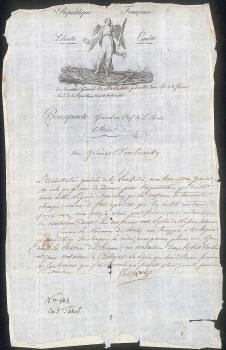

In a letter dated May 11, 1797 from the headquarters in Montebello, Bonaparte informs General Dombrowski about his order which will be transmitted to him by the administration of Lombardy. The order concerned the organization of the Polish Legions, the deployment of battalions in Bologna, Ferrara and Urbino, as well as their uniforms. Serving in Italy under the French Commander-in-chief, Dombrowski's legionnaires wore Polish uniforms with French cockades. Going into battle, they used their own military standards and their own anthem.

Subsequently, Polish units continued to fight against the combined forces of the 2nd, 3rd and 4th anti-French coalitions in the Napoleonic Wars, as well as during Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812.