Ancient Egyptian Papyri in the National Library of Russia

Denon Papyri. 1827

Dominique Vivant Denon (1747–1825), an engraver, draftsman, writer and diplomat, was a secretary of the French embassy in St. Petersburg under Catherine II. Later he served as Chief Director of the Imperial museums of France, acted as agent for Alexander I in the purchase of paintings and other works of art for the Hermitage, but after the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty, he lost his positions.

Denon accompanied the Egyptian campaign of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798–1801. It appears he was the first to propose that the Egyptians had books in the time of the pharaohs. Seeing a wall painting of a writing priest, he concluded, "It is therefore proved that the Egyptians had written books". "I could not help flattering myself, that I was the first to make so important a discovery; but I was much more delighted, when … I was assured of the proof of my discovery, by the possession of a manuscript itself which I found in the hand of a fine mummy...", Denon writes in his Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt During the Campaigns of General Bonaparte, Chapter "A New Description of the Temple at Medinet-Abu".

And more about it, "I felt that I turned pale with anxiety; I was going to express my indignation at those who, despite my constant requests, had violated the integrity of this mummy, when I suddenly perceived in its right hand, and also under its left hand, a roll of papyrus that I should perhaps had never seen without this violation; my voice has changed me. I blessed the avarice of the Arabs, and above all – my good fortune, which put me in the possession of this happy find; I did not know what to do with my treasure, which I hardly dared to touch for fear of injuring of this sacred manuscript, the oldest of all the book in the known world. I could not venture to entrust it to anyone, or to put it somewhere. And all the cotton of my bed was devoted to wrapping it up with the utmost care."

Denon then discusses its contents, "Was it the history of this personage, the remarkable events of his life? Was the period ascertained by the date of the sovereign under whom he lived? Or did this presious roll contain maxims, prayers, or a history of some discovery? Forgetting that the contents of the books was known to me no more than the language in which they were written, I imagined for a moment that I was holding in my hands a compendium of Egyptian literature...".

But still Denon guessed right, as if he could read an inscription of ten hieroglyphic characters on the back of the scroll, “Ta medjat Amduat” - “The Book of Amduat” (“The Book of What is in the Underworld”). He also placed these hieroglyphs on his engraving, to the right of the reproduction of the front of the scroll. In addition, Denon received from the "citizen Amelin" another scroll, the origin of which remained unknown to him. Denon also had one more scroll, larger in size. From the time of the publication, the scrolls became known as the Denon papyri, but traces of them have been lost. It was long unknown that at least two of them came to Bernardino Drovetti (1776–1852) and that he sent them to Russia.Born in Piedmont, living in Turin, Drovetti served in the French army during the Italian campaigns and accompanied Bonaparte to Egypt. In 1803, he was appointed French Consul of Egypt. In 1814, after the fall of Emperor Napoleon, Drovetti lost his position, but in 1820 he was again sent as Consul to Egypt. In addition to diplomatic duties, Drovetti was very actively engaged in collecting Egyptian antiquities. was also busy collecting Egyptian antiquities. In 1824, he decided to sell his vast collection (5,000 items), but demanded such a large sum for it that neither King Louis XVIII of France nor Emperor Alexander I of Russia found it possible to buy it. In 1825, the Russian treasury paid for a large collection of antiquities by Carlo Ottavio Castiglione for the Egyptian Museum at the Kunstkamera; later it entered the Hermitage. The Drovetti collection was acquired by Charles Felix, King of Sardinia, a buffer state between France and Italy. At the same time, he created the Egyptian Museum in Turin, which now houses the second largest collection of Egyptian antiquities in the world after the Cairo Museum.

Meanwhile, Drovetti amassed a second collection, which he also intended to sell and, in order to attract buyers, in 1827 he presented the King Charles X of France with a huge granite naos of Pharaoh Amasis, donated jewelry from Muhammad Ali to the Louvre and two papyrus scrolls to the Emperor of Russia. Nicholas I, like his predecessor, refused to buy the collection of Egyptian antiquities, which, to the delight of Champollion, was bought by Charles X of France for the Louvre

By order of Nicholas I, the ancient Egyptian papyri were transferred to the Imperial Public Library, and documentary evidence of this is a сase kept in the Russian State Historical Archive.

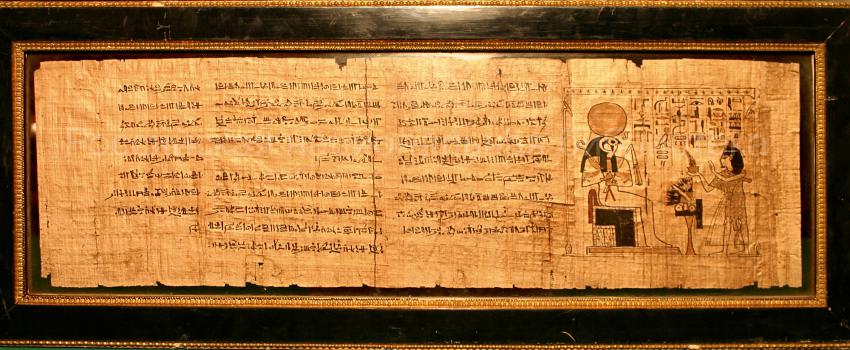

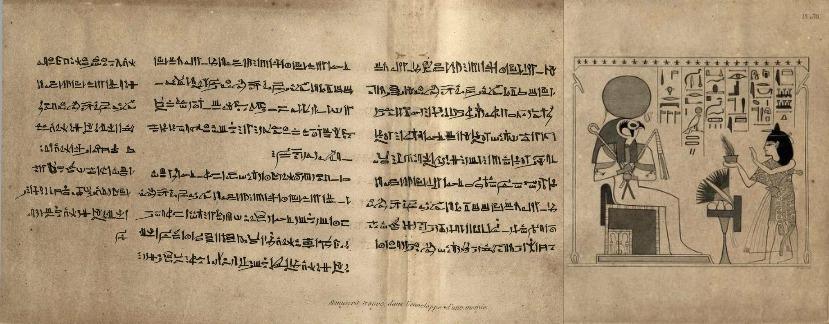

First Denon Papyrus

The Book of the Dead of Oscorkon is a scroll inscribed for the priest of Amun-Ra named Osorkon, a son of the high priest of Amun, Shoshenq. The priest shares the royal name Osorkon. The Osorkons I–IV were pharaohs of 22nd–23rd Dynasties (c. 945–715 BC), ruling Egypt during the Third Intermediate Period. Shoshenq was also the name of many ancient Egyptians, both rulers and commoners.

The priest Osorkon in panther skin clothes is shown in the picture on the right. He offers a bowl of sprouted spelt grains to the falcon-headed god Ra-Hor-akhty sitting on the throne. The god of the sun is presented with the solar disc above his head, his body is covered with mummy wrappings, arms crossed on his breast, holding the crook and flail, symbols of power. Between the priest and the god is an offering table with loaves and two lotus flowers. Above the drawing is written "The divine word of the head of the gods", uttered by the god Ra-Hor-akhty, and his spell which mentions the name of the priest Osorkon, a son of the high priest of Amun, Shoshenq.

Written in a hieratic script, the text contains extracts – chapters from The Book of the Dead, ensuring the deceased's well-being in the afterlife. Two of the three chapters are dedicated to the heart: according to the Egyptians, it will be weighed on a scale against a figure of Maat, the goddess of truth. In chapter 30 of The Book of the Dead, the deceased appeals to the heart not to testify against him in court, that is, not to weigh more than Maat. This is followed by a spell from chapter 29, guarding against the theft of the deceased's heart by "those who steal hearts". The last part contains a hymn uttered by Osorkon to the sun set over the horizon, associated with the deceased king Osiris (a variant of the hymn for chapter 180.

Studying the papyri published by D.-V. Denon in 1802 in the atlas-appendix to the Travels in Egypt, J.-F. Champollion identified the names of Osorkon and Shoshenq and converted their hieratic writing into hieroglyphs. Further, he came to the conclusion about the the equivalence of hieroglyphic and hieratic systems, and, comparing the names of Osorkon and Shoshenq from the Denon papyri with those found in other ancient Egyptian texts, both hieroglyphic and hieratic, he noticed that these names were often found equally among grandfathers and grandchildren, which indicates that such a family custom was common.

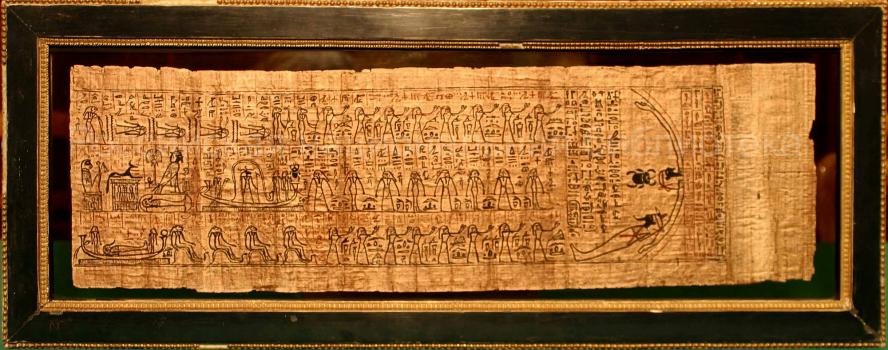

Second Denon Papyrus

The Book of Amduat of Osorkon is a scroll inscribed for the priest of Amun-Ra named Osorkon, a son of the high priest Shoshenq and grandson of Osorkon I (c. 924-889 BC). The name of the pharaoh is enclosed into a cartouche and is accompanied by the words "endowed with life like Ra forever", which give reason to believe that Osorkon I was still alive when his namesake grandson died.

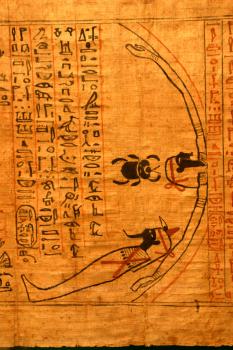

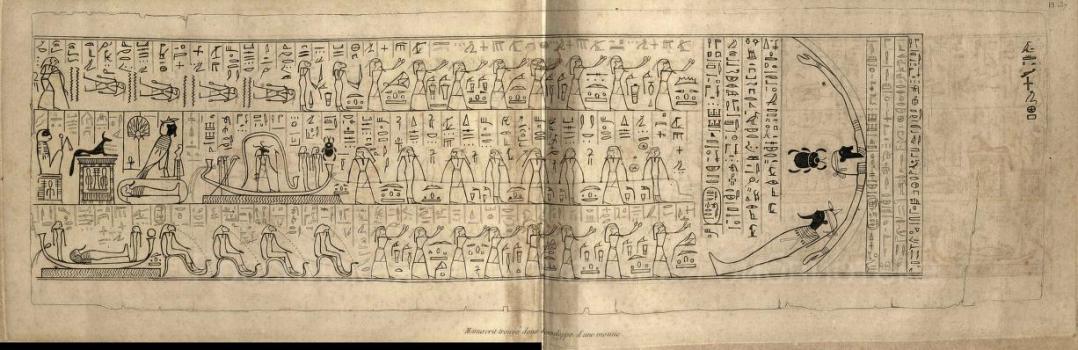

On the back, left hand side of the scroll is the title, The Book of Amdaut. Meanwhile, the scroll constitutes a compilation made up of various fragments of this book, consisting of 12 parts, according to the number of night hours of the sun's sailing path through the underworld from sunset to sunrise. The drawings on the scroll refer to the final hour just before dawn, when the sun moves towards the exit from the underworld.

Afu-Ra, a night aspect of the sun god Ra, is depicted as a ram-headed deity in his solar boat in the middle row, slightly to the left of the center. Above Ra is a curved snake Mehen, the god of time, on the bow of the boat is a scarab beetle Khepri, a symbol of the morning sun. The boat is being dragged by eight people towards the horizon. Eight figures each in the lower and upper rows with raised hands greet the rising sun personified by Khepri which is “blown out” by the wind god Shu. On his arm, at an angle, lies a mummy with a lotus bud and a cone-shaped jar on its head. The mummy is a personification of the body of Osiris, the god of resurrection and immortality, with whom the deceased priest is identified. Like Osiris, he is being left in the underworld during the sunrise.

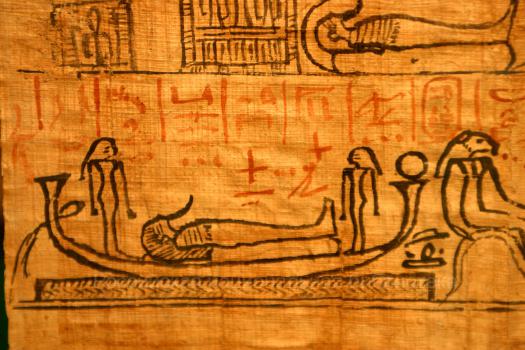

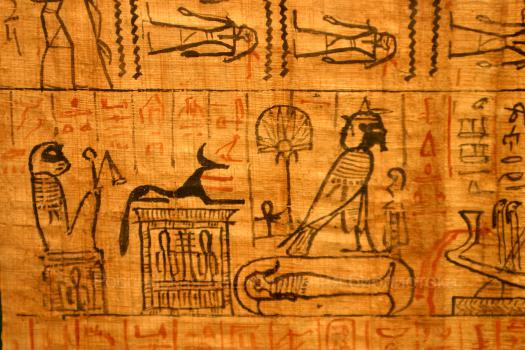

In addition to the main plot, the falcon-headed god Horus is shown in the upper row on the left, looking at the “four lakes” and four lying figures, which probably serves as a call from the god to the drowned to get out of the waters, using the power of the sun rising from the underworld. The left side of the middle row features the monkey-headed god Thoth, the god Anubis portrayed as a jackal, and the mummy of the deceased. Above the mummy is a soul depicted as a bird with a human head, a fan representing the concept of the “shadow”, close to the soul, as well as the hieroglyphs of the west, a symbol of the realm of the dead. In the bottom row you can see a boat with the body of the deceased Osiris and the standing figures of his wife Isis and sister Nephthys. Lion-headed goddesses sitting on snakes, breathing fire from their mouths, destroy the enemies of light and clear the way for the boat.

In the text, the priest Osorkon is called Osiris and is attributed with positive traits. Next come the usual magic formulas and a spell that enables Osorkon's soul to see the sun and follow Osiris.