Samarkand Quran

O. Vasilyeva

Reproductions

In 1898, a folio from the Samarkand Quran was published in 2000 copies. There is known a replica of the initial page printed on fabric. It contains part of the Surah 2 (the very beginning of the Samarkand manuscript is missing). This souvenir piece of cloth came in the Asian Museum (now the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts) together with an extensive collection of the historian N.P. Likhachev. The fabric may be rolled up and folded for easy carrying as an amulet. It is surprising that for such a purpose a late paper sheet was copied, and not a parchment one.

There is at least one complete photographic copy of all pages of the Quran, which is now in the Russian State Archives of Ancient Documents in Moscow. It is possible that a photocopy was made to prepare a facsimile edition, although it isn't clear exactly which one.

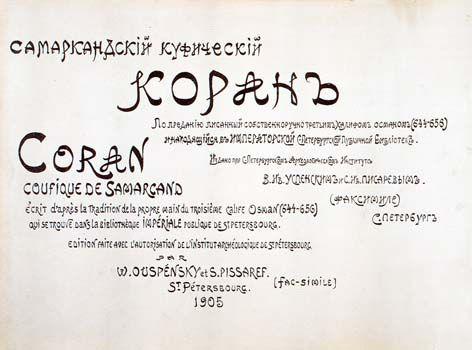

Lithographed Facsimile Edition

The idea of publishing the Samarkand Quran was in the air, as the saying goes. Not later than 1902, the issue of facsimile reproduction by lithographic method arose. Part of official correspondence on this issue can be found in the Department of Archival Documents of the National Library of Russia. The first in time is a letter from Tashkent to the Administration of the Imperial Public Library, dated March 2, 1902, signed by Acting Director of the Turkestan Public Library and Museum Iosif Plyatt (1852-1904).The letter reads, "In view of the information about the publication of a limited number of copies of the Uthman Quran, held in the Imperial Public Library, for acquiring which the Library does not have the means due to its high cost, and meanwhile it would be extremely necessary to have this shrine of Islam here, let me apply to the Administration with the most humble request, whether it will be considered possible to provide our library with this valuable publication for free, in memory of the fact that the Imperial Public Library is entirely indebted to the unforgettable organizer of Turkestan, K. P. von Kaufmann for possessing the original of this Quran".

From St. Petersburg came the reply, "…The Administration of the Imperial Public Library has the honor to inform you that the Uthman Quran was published not by the library, but by private individuals who promised to donate two copies of the book to the Library. Upon receipt of these copies, the Imperial Public Library will donate one of them to the Turkestan Public Library".

From other documents we learn that the publication, one copy of which was valued at 500 rubles, was undertaken by "an assistant clerk of the Board of the People's Teachers' Pension Fund, who does not have a rank", "the head of the Museum of the Archaeological Institute" Vasily Uspensky and "St. Petersburg Merchant Semyon Pisarev". (Semyon Pisarev, contrary to some unknown opinion, was not an Arabist. The merchant of the second guild sold fabrics in his own shop on Staro-Nevsky Prospekt and at the same time took part in publishing activities under the auspices of the Archaeological Institute.) They were allowed to publish 50 copies and were obliged to provide two of them to the Imperial Library. The conditions were met, and when the library received two copies, one of them was sent to Tashkent on December 5, 1904. Thus, it is clear that the facsimile of the Samarkand Quran was published in D. Rudnev's Cartographic Establishment before 1905 indicated on the title page. Its text again brings us back to the old legend, “The Samarkand Quran, according to legend, was written by the third Caliph Uthman (644-656) in his own hand, and is housed in the Imperial Public Library. Published at the St. Petersburg Archaeological Institute by V. I. Uspensky and S. I. Pisarev (facsimile)».

This publication is the fourth in a series of unique manuscripts of the Holy Scriptures held in the Public Library. Among them are the Codex Sinaiticus – the earliest surviving Greek version of the Bible, dating 4th century, The Last Prophets – the oldest dated Hebrew manuscript of 916 and the Ostromir Gospels – the earliest dated Russian book of 1056–1057. Together with the Samarkand Quran, V. Uspensky planned to publish the Greek Purple Gospels of the 6th century, but this attempt was not successful.

The archive of the National Library of Russia also contains a letter from the Minister of Education V. G. Glazov to Director D. F. Kobeko, dated July 16, 1905, which states that Uspensky and Pisarev "provided two copies of the said publication to the Minister of Foreign Affairs; Count Lambsdorff, recognizing this publication as a rich contribution to science, asked me to help Uspensky and Pisarev receive the highest award for their useful work…»In order to confirm the scientific significance of the publication, Kobeko writes in a draft response letter, among other things, “This manuscript constantly attracts the attention of foreigners and natives of the Turkestan region, visiting the library. This manuscript has now been published as a facsimile at the expense of Messrs. Uspensky and Pisarev. This edition makes it available for study… by scholars of the Quranic text, as well as Arabic philologists and paleographers. I have to admit that Messrs. Uspensky and Pisarev did a great service to Oriental science by publishing this manuscript.».

Emir Sayyid Abd al-Ahad Khan of Bukhara and his heir Mir Muhammad Alim received one facsimile edition for each as a gift. (Сopies of the book are now in the National Library of Uzbekistan, in the State Museum of the History of Uzbekistan, in the State Museum of the History of the Timurids, in the library of the Muslim Board of the Republic of Uzbekistan in Tashkent). The publication was also presented to Shah Mozaffar ad-Din of Persia, Sultan Abdul Hamid II of the Ottoman Empire and, of course, Emperor Nicholas II of Russia. Apparently, the latter copy is now held in the Scientific Library of the State Hermitage. In total, the printed Samarkand Quran is available at least in four institutions of St. Petersburg, namely in the State Museum of the History of Religions, in the library of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts and in the Asian and African Department of the National Library of Russia (one copy was received immediately after publication, and the second is part of the memorial library of Academician-Arabist Ignatiy Krachkovsky, which was given by his widow, Professor Vera Krachkovskaya in 1973). There are also copies in the Moscow Cathedral Mosque, the Yardyam Mosque in Otradnoye, the Nizhny Novgorod Mosque, the National Museum of Arts of Azerbaijan, in the Columbia University and the Berlin State Library.

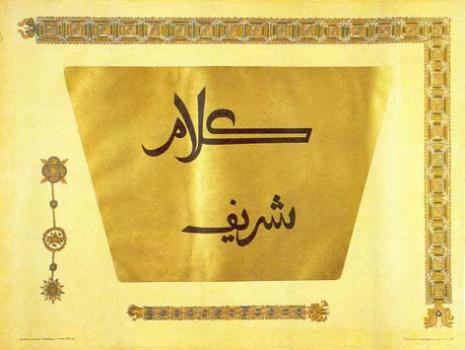

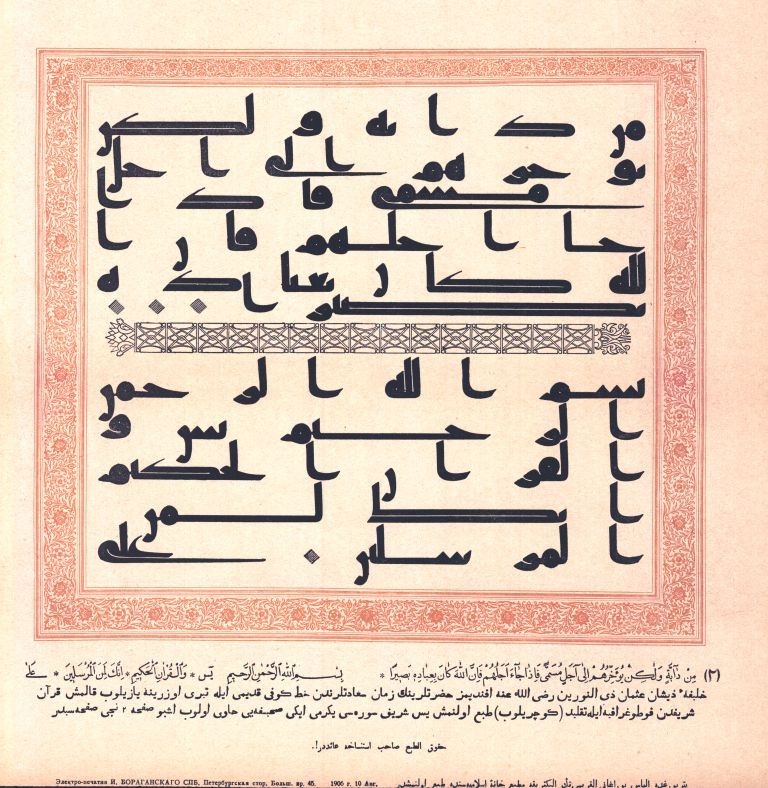

Publication of Surah Ya-Sin

In 1906, the St. Petersburg Electro-printing House of Ilyas Boragansky published Surah Ya-Sin of a reduced size from the Samarkand Quran. A native of Bakhchisaray, Ilyas-Murza Boragansky (1852–1942), who studied calligraphy and engraving in Istanbul, was invited to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a calligrapher in 1883. In 1894, Boragansky became the owner of a typolithography, where he published books in Oriental languages. Boragansky was involved in the publications of Oriental texts even before. For example, in 1891, he prepared the Reading Book Exemplary Works of Ottoman Literature in Extracts and Fragments by V. D. Smirnov for publication. The author expresses gratitude to him on page XIV of the preface.

Printed proofs of the pages from this edition are kept at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences in the archive of V. D. Smirnov, who, among other things, acted as a censor of Tatar books. The original text, reproduced with the retrieval of lost areas along the inner margin, but without the colorful verse markers, is enclosed in an ornamented bronze-colored frame. At the bottom of each page is the text of the same passage, typed in modern Arabic and its translation into Tatar. Obviously, this publication had a certain educational goal. It enabled Tatar Muslims to read the most important surah of the Holy Book, understanding what exactly is written in the ancient Kufic script on one page or another.

When finished, the book has an ornamented title page and a finely designed lengthy introduction from the publisher, inscribed in an oval. As we learn from the introduction, Boragansky examined some of the Oriental manuscripts of the Public Library, including the Quran of Caliph Uthman, in 1889. Boragansky described in detail the appearance of the book, its sizes, ink and handwriting. The same year, he decided to print a photocopy of the Quran, so all 706 folios were photocopied. (It is possible that this particular photocopy is held in the Russian State Archives of Ancient Documents.) The printing plates of the book were made from photographs using the zincography method. However, the facsimile edition of the entire Quran was printed, as mentioned above, by D. Rudnev's Cartographic Establishment, and Ilyas Boragansky limited himself to Chapter 36 of the Quran (Surah Ya-Sin).