Design of Soap Wrappers in Leningrad in the 1920s–1930s

Yartseva A.V.

History of the LenZhet Trust (1921-1930)

The Petrograd State Soap and Fat Trust was founded in the city on the Neva in December 1921. In 1924, when it changed its name to the Leningrad State Soap and Fat Trust it still consisted of three production facilities established before the October Revolution of 1917. The first is the Karpov Soap Factory (285, Ligovskaya st.1) , the former Factory of A. M. Zhukov, officially registered in 1865. The company was given the name of one of the organizers of the Soviet chemical industry Lev Karpov. Since the 1990s, it has been continued as the firm "Aist". The second is the Leningrad Chemical Laboratory (27, Red Commanders Pr.2). This is the former St. Petersburg Chemical Laboratory established in 1860. And the last one is the Salolin Hydrogenation Plant (56, Novo-Mikhailovskaya st.3 ), which name comes from the solid fats used to make soap, founded in 1912.

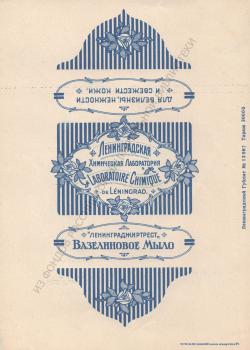

The earliest examples of Soviet industrial graphics, cared for in the Prints and Photographs Department of the National Library of Russia (NLR), date back to 1924. These paper soap wrappers are produced by the Leningrad Chemical Laboratory. They were made by colour lithography in the E. Sokolova State Printing House, the former typolithography of the A. F. Marx Partnership, located in the house next to the Chemical Laboratory (29, Red Commanders Pr.) 4). The wrappers were designed after the renaming of Petrograd to Leningrad, which occurred at the end of January 1924, and were received by the Library in August, November and December of the same year from the Leningrad branch of the State Publishing House of the RSFSR, also known as Gosizdat 5.

Soap of Beauties, Oriental, Fatma, Heliotrope soap wrappers were made in the Art Nouveau style, with a print run of 30,000 copies. The wrappers of Vaseline Soap (30,000 copies) and Baby Soap (20,000 copies) also evoke images of the early twentieth century, and not at all the Soviet period.

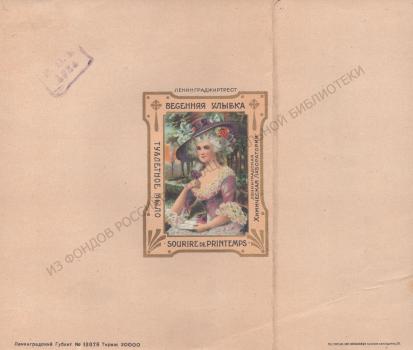

The fact that "modern small printing follows its pre-revolutionary predecessor"6, in the 1920‑1930s was often denounced in periodicals. The poet Nikolai Aseev asked the question, "Have the covers of our state goods changed in accordance with the shift in tastes and sympathies that has occurred in the country? Who likes the smell of a plump beauty laced into a corset, wearing a wig and a hooped skirt coming out far back?"7. As the author suspected, not only the manufacturer, but also "the consumer of this soap, miss the days of crinolines and wigs."8.

N. Aseev also criticized the presentation of oriental motifs on the packaging, since the East, fighting for the renewal of everyday life, was "depicted… according to the traditions of fairy tales, the traditions of opera and ballet”9. The article also condemned inscriptions made in a foreign language, "… The name is given in French, apparently in hopes of a privileged idiot"10.

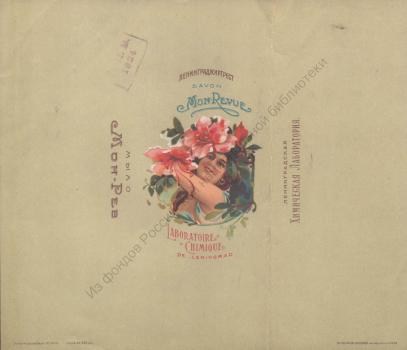

Although the indignation of N.N. Aseev was caused by Moscow products dating the late 1920s, his words are remembered when looking at the wrappers printed in 1924 for the Leningrad Chemical Laboratory. In addition to the already mentioned soaps, these also include Spring Smile (“Sourire de printemps”, 30,000 copies) and Mon-Revue (25,000 copies). On the last wrapper, the French version of the title is written as “Mon-Revue”, but probably meant “My Dream” – "Mon-Rêve".

You should keep in mind that at that time there was a provision in which all "perfumes and cosmetics, except sanitary and hygiene items"11 officially were included in the "second group" of luxury goods.A list of such goods appeared on the pages of the Pravda newspaper in January 1923. It was opened with items made of gold, platinum and precious stones, complemented by fresh flowers and ornamental plants. However, after a year and a half, only “foreign perfumes and cosmetics” 12 remained on the list of luxury goods. In 1925, "The government of the USSR excluded all domestically produced perfumes and cosmetics from the lists of luxury goods …, and it was rightly recognized that perfumes and cosmetics are already consumer goods at a certain cultural level of the population."13.

At that time, the Soviet soap industry had a space for great development: the average soap consumption was extremely low. "The majority of the population…in the USSR use laundry soaps as toilet soaps, i.e. for daily washing and bathing. The reason for this is the cheapness of this soap compared to toilet soap, as well as the poverty and modest needs of the general population of the country." 14. The cited publication of 1926 also reported, “How little in our village they consume goods usual for the city, for example, for each resident of our Union, on average, there is only half a piece of toilet soap per year. Increasing this tiny amount to a whole piece per capita should already double the production of toilet soap in the Union.15

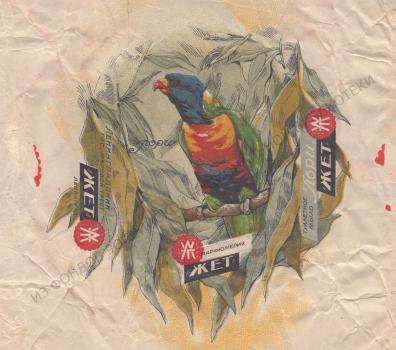

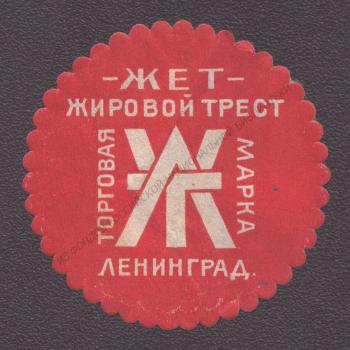

Meanwhile, the Leningrad Soap and Fat Trust was expanding: in 1925 it merged with the Nevsky Stearic Plant (48, Smolenskogo Pr. 16). In 1926, its name was reduced to the Zhet trust. Advertising its brand, the trust produced Zhet toilet soap in a wrapper designed in the spirit of constructivism, on which the brand name was repeated six times, in different sizes. A red wax seal served as a background.

The new abbreviation was made up of the vowel consonant “Zh” (“Fat”) and the letters “t” ("trust").

The change in the name of the trust led to changes in packaging design, for example, in the already mentioned Mon-Revue soap. Also significant are the growth in print run, suggesting an increase in production: if in 1924 the wrapper for the Leningrad Chemical Laboratory was printed in the number of 25,000 copies, then in 1927, the Zhet trust I have already ordered 60,000 wrappers with a similar design from the E. Sokolova Typo-lithography.

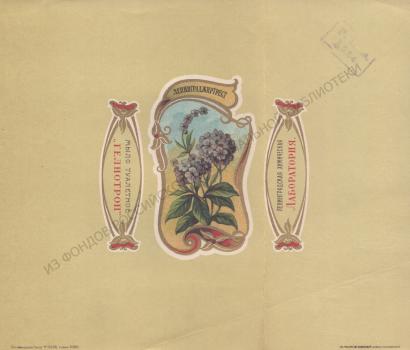

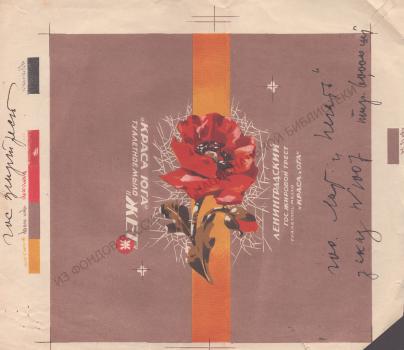

The collection of the National Library of Russia possesses not only the original packaging of the Zhet trust products, but also several proof prints with handwritten notes. They come from the Lithography "Pechat" of the Graphic Business trust (the former Typo-lithography of Wefers and Co., which was supposed to release 60,000 copies of soap wrappers with images of flowers: Beauty of the South (poppy), Everyone knows me (chamomile) and Pansies (later the name of the soap was changed to «Ivan and Marya»).

In the second half of the 1920s, the Leningrad trust produced 11% of the all-Union production of perfumes, cosmetics and toilet soaps. The largest manufacturer of these products in the USSR was then "TEZHE" – Moscow State Trust of the Fat and Bone Processing Industry "Fattiness". His trademark was registered on September 30, 1926. (initial registration took place on March 22, 1924)22.

Three months after the registration of the "Zhet" trademark, on March 31, 1927, in the newspaper Evening Moscow published the article “Dispute between the trusts “TEZHE” and “ZhET”. Before quoting it, one clarification needs to be made: at the turn of the 1920s-1930s. the word "Three months after the registration of the “Zhet” trademark, on March 31, 1927, in the newspaper “Evening Moscow” the article “Dispute between the trusts “TEZHE” and “ZhET”. Before quoting it, one clarification needs to be made: at the turn of the 1920s-1930s. the word "etiquette" denoted not only rules of behavior and treatment. It continued to be used in the meaning it had in the second half of the 19th century and at the early 20th century, "A piece of paper with the designation of the company, price, name of the product, etc., pasted on the product" 23.An article about the conflict between the trusts wrote, A dispute unprecedented in the practice of state-owned enterprises broke out between the state trust “Fatness” ("TEZHE") and the Leningrad Fat Trust, which patented the "ZHET" brand, which at a quick glance is very similar to the "TEZHE" brand. … Trust “TEZHE” initiated by the Higher Arbitration Commission at EKOSO RSFSR24 the case of imitation. The prosecutor's office has also drawn attention to this. <…> Manager of the trust “TEZHE” Comrade G.N. Larionov … stated that the trust “TEZHE” Consider the action of the Leningrad Fat Trust as competition, completely unacceptable under Soviet conditions. Comrade Larionov said, "First, Leningradsky Fat Trust imitated our product labels (font, name and paint), and now he has copied our brand. All this misleads the consumers and lead the TEZHE to losses. We have many disgruntled, misled buyers of the ZET products who complains about supposedly our product. In addition, for example, the Leningrad Fat Trust has recruited many artisans who counterfeit our labels and goods. Of course, we cannot accept this situation." 25.

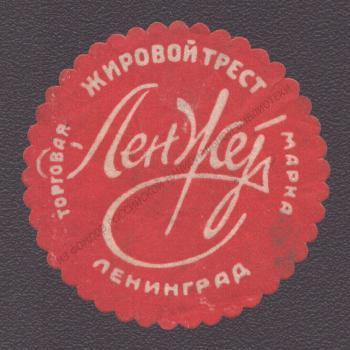

As a result of these proceedings, on September 27, 1927, the Leningrad State Fat Trust, which produced soap, perfumes, cosmetics, glycerin, glue, bone meal and candles, registered a new trademark "LenZhet"26: the first syllable "Len‑" (Leningrad) was added to the previous abbreviation "Zhet". It could no longer arouse any suspicion of resemblance to the "TEZHE" brand; its design was significantly redesigned in comparison with the "Zhet" brand, as well as with the earlier brand of the Leningrad Soap and Fat Trust. (It is interesting that on April 3, 1928, "TEZHE" registered another one brand, which also abandoned the composition of strict chopped letters in favor of the elegant handwritten font.

The change of the trademark and the abbreviated name of the Leningrad trust again led to a change in the text on the wrappers, the design of which remained unchanged. This happened, for example, with the Spring Smile soap 27, which was issued by Leningrad Fat trest back in 1924. Differences in the design of the "Zhet" wrappers and "LenZhet", relating to the name of the trust and its brand, are also noticeable in the example of one of the cheapestsoap – Apple (or Paradise Apple), a dozen pieces of which cost 1 ruble 80 kopecks (15 kopecks per piece) in 1928.

Due to supply disruptions, LenZhet completed only 63.8% of the task to produce toilet soaps in the 1926/27 business year. However, in general, at the end of the year, the trust gave itself a high assessment, "Laundry soap, glue and gelatin are unmatched in quality. Our toilet soaps, perfumes and cosmetics have also improved over the past year, and with rare exceptions we have no complaints about the quality. A lot of work has been done and still needs to be done in terms of decoration and elegance"28.

The LenZhet trust increased production of perfumery and cosmetics dozens of times compared to five years ago: from 1,764,000 items in 1923/24 to 46,800,000 items in 1927/28. 90,000,000 items were planned for 1928/29. The trust's price list explained: "Such exceptional growth in production was caused by the ever-increasing demand of the general public for LenZhet products, the quality of which was constantly improving both internally and externally."29.By 1928, the Leningrad Chemical Laboratory began to be called the Perfume Factory No. 4. By the next year, the Aromatic Substances Factory was added to the trust's production facilities (6-b, Predtechenskaya Street) 30.

In the second half of the 1920s, the Leningrad trust also had a branch in Moscow. At first it was located in house No. 11 on Tretyakovsky Proezd, by 1929 it moved to Red Square, to the Upper Trading Rows (now State Department Store) 31 , but from October 1, 1929 was liquidated32.

By 1930 LenZhet was under the jurisdiction of Leningrad Regional Council of National Economy (LOSNKh) which organized, directed and controlled industry and trade. The board of the trust, previously located in house No. 19 on Fontanka Embankment, and then in house No. 24 on Herzen Street33, moved to house No. 71 on Marata Street34. When the trust was founded it employed approximately 300 people35, now a total of about 2,000 workers and support staff were employed at the trust’s seven enterprises located in different parts of the city. Of these, 652 people worked at the Nevsky Soap Factory (former Nevsky Stearin Plant), 429 – at the Bone Processing Plant, 369 – at the Perfume Factory No 4, 209 – at the Karpov Soap Factory, 187 – at the Salolin plant, 144 – at the Gelatin Plant, 73 – at the Aromatic Substances Plant No. 7.

![[Trade mark of the TEZHE trust, Moscow: fragment of the Soap of the Four Aces wrapper”]. [Trade mark of the TEZHE trust, Moscow: fragment of the Soap of the Four Aces wrapper”].](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA7596/s_NA76330.jpg)

![Soap-fat trust. Leningrad: [trademark]. Soap-fat trust. Leningrad: [trademark].](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA7596/MA70576/s_NA76331.jpg)

![LenZhet : [wrapping paper]. LenZhet : [wrapping paper].](/ve/dep/artupload/ve/article/RA7596/MA70592/s_NA76348.jpg)