Quran Manuscripts

Arts of the Manuscript Book

Most Quran manuscripts in the Library's collections have siginficant artistic and historical value. This is particularly true for all 130 fragments of early Qurans from the J.-J. Marcel Collection.

These are complemented by two items from the P. Dubrovsky Collection: a parchment leaf of small format and a manuscript containing a portion of the Quran, juz 29 (Дорн 6). Dubrovsky described this manuscript as "the most precious landmark, written in Kufic letters, which, according to ancient tradition, is believed to have belonged to Fatima, the daughter of the prophet Muhammad. This Quran exists, exactly as Muhammad originally preached it. It is known that his father-in-law Abu Bakr, after the death of the lawmaker, collected scattered leaves of the Quran and compile them into one book, full of repetitions and contradictions". Meanwhile, this Quran could not have belonged to the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad. The earliest Holy Books were written in the Hijazi script on large sheets of parchment at the late 7th century, they had vertical formats. By the writing style and small horizontal format, as well as by the type of illumination, the manuscript cannot be dated to earlier than 10th century. As evidenced by double-page illuminated frames at the beginning and at the end of the text, the copy of the juz was initially intended to be bound into a separate volume. In the 19th century, the manuscript was given our library binding. The spine and the corners of the book are covered with leather, while the rest of the binding is old brocade — violet silk embroidered with silver threads.Two paper manuscripts employ the New Style handwriting (Broken Cursive). These are a fragment of two leaves (Марсель 111) and a defective copy from the Archimandrite Antonin Collection (АНС 106). The latter is written on paper with hardly visible cain lines, widely spaced no less 10 cm apart. The manucript is decorated with colourful verse and section markers in the form of marginal ornaments that contain words written vertically. Thus, groups of five verses are marked with the word khamsah ("five"); each ten verses, a juz (one thirtieth of the Quran) and a sub (a seventh part) are indicated with their numbers. The origin of the Quran manuscript from Egypt may be detected from these marginal inscriptions that are stylized to resemble the ornaments of Coptic manuscripts of the 9th-12th centuries. It is impossible to date the manuscript on the basis of illumination alone, but the writing style may point to the 12th century.

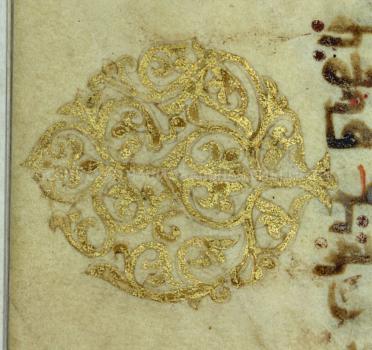

Distinctive decorative features of Quran manuscripts from the easternmost regions of the Islamic world are found in a copy made presumably in the 13th century, most likely on the territory of Khorasan or present-day Afghanistan (Дорн 12). It is written in large Muḥaqqaq script, with gold rosettes separating verses. Gold marginal medallions highlight titles of chapters, the start of each juz, hizb and a group of ten verses. The original opening leaves of this Quran are lost, but folios 163v—164 constitute the double-page illuminated composition. Each of these two folios contains eight lines of text surrounded by an ornate frame. The frame is comprised of the top and bottom rectangular panels and vertical side interlaced bands. The outer margins are adorned with three round medallions and two teardrop-shaped ones. Obviously, the book once began with a similar frontispiece.

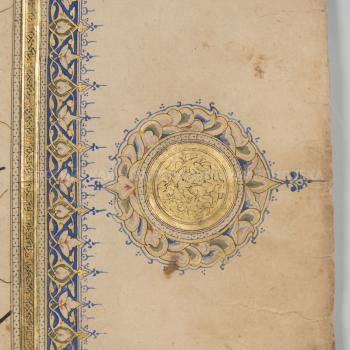

During the 14th-15th centuries, the Mamluk style of decoration was developed in Egypt and Syria. It was used in the manuscripts made for Mamluk sultans and high officials. The four key characteristics of the style include clear-cut geometric designs, an abundance of gold and blue colours, large elegant Muhaqqaq, Rihani (Rayhani) or Thuluth scripts, the use of thick yellowish glossy paper with vertical lines (pontuseau). Good examples for the Mamluk style are a large-format complete Quran of the 14th century, featuring the surviving left side of a double-page frontispiece (Марсель 132), and fragments of juz 23, probably created in the 1340s (Дорн 10).

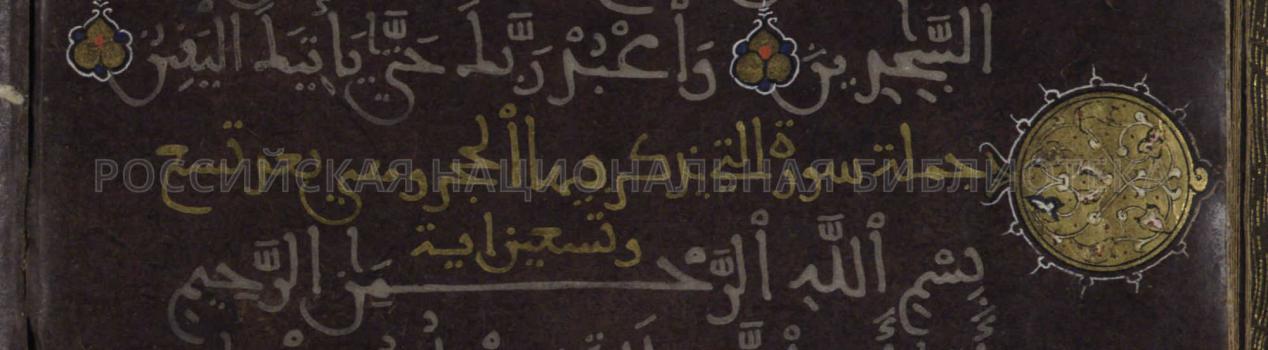

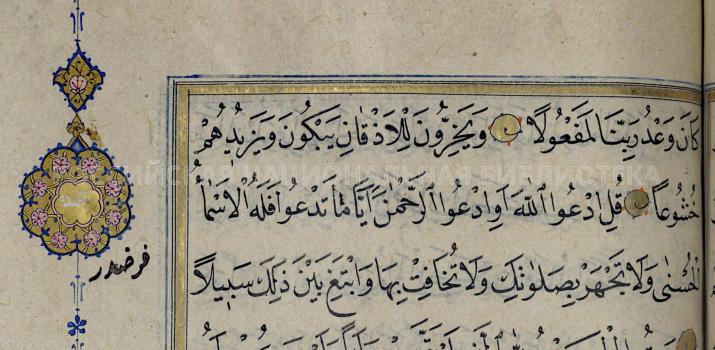

The latter is a richly illuminated manuscript (Дорн 10) that exhibits the extraordinary level of decoration. The two initial decorated pages of the manuscript are particularly embellished. Each page has three lines of text, framed with a gold interlaced border. The top and bottom rectangular panels contain cartouches, in which verses from Surah 56 ("The Inevitable") are inscribed in Kufic script (56: 76–79), "Surely it is a bounteous Qur'n, In a book that is protected, Which none touches save the purified ones. /[It is] a revelation from the Lord of the worlds". Round medallions, which are placed on both sides of each cartouche, carry phrase in gold, "The beginning of the twenty-third juz out of the division into 30 juzes".There are many styles of Arabic calligraphy. A copy of the Quran was written in Maghribi script in North Africa at the turn of the 14th–15 centuries. Four volumes of it now belong to the National Library of France, but fragments from them, bound into one volume, reside in the collection of the National Library of Russia (Дорн 41). An endowment inscription states that this Quran was donated by the ruler of the Hafsid state, Abd al-Aziz, to the Kasbah mosque in Tunisia in 807/1405. The manuscript's owner P. P. Dubrovsky wrote about it, "Some chapters of the Quran are written on paper, called charta bombycina (cotton paper), of diverse colours, in gold and silver letters; the manuscript is dated back to ancient times". The text is transcribed in silvery-white ink. Written in gold, chapter titles are marked with gold medallions in the margins. The paper is coated with an artificial dye comprising blue, red and yellow pigments, a mixture of which makes different shades of brown to very dark, reminiscent of purple. This Quran is a rare example of decorative art.

The Library's manuscript holdings include a wide range of Qurans dating from the 16th century onwards. They came from different regions of the Muslim world and exhibit a broad variety of decoration and script styles based on local customs.

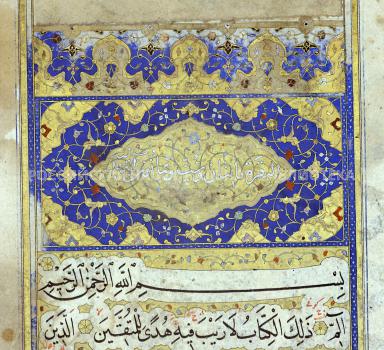

For instance, most Iranian manuscripts created during the Safavid dynasty (the 16th-17th centuries) are richly decorated, mainly in blue and gold. The opening of the books was embellished with double-page elaborate ornaments that occupied large portions of the pages, leaving only small "windows" for the text.

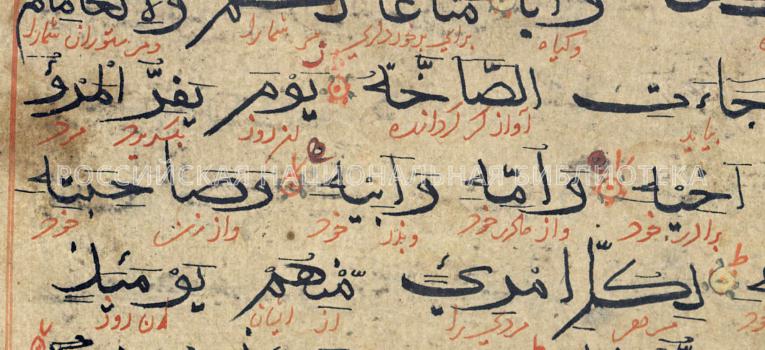

The manuscript's decoration is dominated by floral motifs and cloud bands inspired by Chinese art, which form fancy knots and bows. This decoration style is exemplified in a manuscript copied by Husayn al-Katib in 945/1538-1539 (АНС 357), as well as in a copy, dated 1001/1592 (АНС 1), covered with a well-preserved lacquer binding.Some copies of the Quran have Persian or Turkish translations inserted between Arabic lines. Persian was a spoken and literary language not only in Iran, it also spread through the Muslim-majority areas of India. Therefore, it is not surprising that we find Persian translations in a manuscript (АНС 14) produced around the 16th century in this region as evidenced by Bihari script, which was typical of India during the 14th-15th centuries. Interestingly, in the 19th century this Quran was found in Central Asia, as indicated by the seal of Khudayar, Khan of Kokand (ruled from 1844 to 1858, from 1862 to 1863, and from 1865 to 1875).

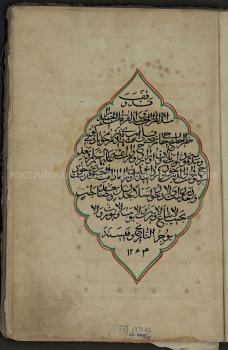

As usual in Central Asian Qurans of the mid-19th century, a manuscript, dated 1275 / 1858-1859 (АНС 282), begins with a frontispiece, richly illuminated in gold and striking blue and orange colours. This Quran was likely copied and decorated in Khiva.

From the 16th century onwards, the cursive Naskh script was the most often used for copying the Quran, and the once popular Muhaqqaq practically disappeared from the pages of books. But unusual deviations from the general rule can be encountered in the periphery, far from the important centres of manuscript production. Such exceptions include a huge Quran made in 1025 / 1616 (АНС 85), probably in the Caucasus. The manuscript was written by Ahmad b. ‘Ardur in large calligraphic Muhaqqaq script. At the same time, this copy is decorated with a rather simple frontispiece, executed in black, green, yellow and red.

Several Qurans were made in the Ottoman Empire, including a book containing Chapter 6 (Surah Al-An'am, The Cattle) which was calligraphed in beautiful Naskh on yellowish paper in 957/1551 (АНС 667). A Turkish origin is indicated by the opening headpiece - unwan, the characteristic features of the writing style and, most importantly, the elegant leather binding. The delicately gold embossed binding was definitely produced at the same time as the text-block.

Written in Naskh script in 982/1574, a large Quran (Кр. 50) is lavishly illuminated throughout with a double-page frontispiece, surah markers within cartouches, marginal vignettes separating verses and an ornamented colophon. Its Turkish black leather binding of the 18th century, with gilded embossed cornerpieces and centerpieces, needed to be restored. The binding repair was carried out at the National Library of Russia in 1990s.

Several Quran manuscripts are the later Ottoman production. One of them was penned by the calligraphy master Al-Sayyid Muhammad in Karahisar-i Sharki (Şapkarahisar) in 1076 / 1665-1666 (Дорн 8). Copied in an elegant Naskh script, it is decorated with a florid doubled-page frontispiece, headpieces, marginal markers. The manuscript is bound into a leather binding with a gold embossed centerpiece, cornerpieces and medallions which clearly show the traditional Turkish carnation ornament.One of the 18th century Qurans is much more modest (Дорн 39). It features Turkish translations inserted between Arabic lines in red ink. The Quran is written on thin French watermarked paper, which is widely used in Turkey. The watermark presents clusters of grapes. The manuscript opens with a rough headpiece - unwan. A burgundy leather binding has a gilded embossed centerpiece with two small medallions decorated with carnation motifs.

Four leaves from a magnificent large-format Quran (АНС 87), also came in the Library from the Ottoman Empire. From a suviving colophon, we can find out that the manuscript was copied in 1173/1759 by Mustafa al-Majdi b. al-hajj Yusuf, a hafiz (a person who has completely memorized the Quran) and a disciple of the deceased 'famous' ( al-maʿruf) Sayyid ʿAbd-Allah. Perhaps the scribe was taught by the renowned Ottoman calligrapher Yedikuleli ʿAbd-Allah Efendi (1670-1731) who served at the court of Sultan Ahmed III (ruled from 1703 to 1730). The colophon leaf is decorated with a rectangular headpiece filled with interlaiced bands, floral motifs at the top of the sheet and gold embelishments between the lines of text. The initial folio of the manuscript with the right side of a double frontispiece contains the first surah. Gold frames, rosettes of various shapes, separating verses, and surah titles are found on two leaves in the middle of the Quran.

The Scribe Muhammad al-Amin, an imam of the Sufilar mosque quarter, in the middle of the month of Rajab 1218 / early November 1803 completed the most recent Turkish Quran (АНС 277). Copied in minute and neat Naskh script, it opens with a double-page frontispiece embelished with European decorative motifs – images of vases with lush bouquets. A gold embossed brown leather binding has an envelope flap.

The Krachkovsky Collection contains twenty-five Juzes that once were parts of a set of thirty-volume Quran (Кр. 46), copied in 1261 / 1845-1846. All volumes open with a record, dated 1264 / 1847-1848, by Hajji Murtaz-Kuli Badkubi (i.e., living or born in Baku) who bequeathed this manuscript as an endowment (waqf). He stipulated that the reward for reading the book would be given to the souls of the Twelve Imams, as well as the souls of his deceased parents. At the same time, the book must remain in his possession until the end of his life and then be passed on to his descendants from generation to generation (Fig. 9). Each of the Juzes starts with a double frontispiece. Chapter titles are written in gold within frames decorated in gold and colours. In this manuscripts, you can see the ruling in gold. The space between the lines of the Quranic text is filled with golden cloud bands. Identical lacquer bindings of the volumes have survived but are severely damaged.

O. Vasilieva, O. Yastrebova