Quran Manuscript

Talismanic Qurans

Muslims highly revered the Quran as divine revelation. This veneration has led to the belief that the Quranic text has the supernatural power to protect the person who reads or carries it from evil, illness and danger. Some chapters (surahs) and verses of the holy book are considered to be the most effective in certain situations. Therefore, it is not surprising that portions of the holy book are often used as talismans. Protective talismans commonly present paper leaves covered with Quranic verses or short surahs, that are rolled and placed in amulet cases, often made of precious metals.

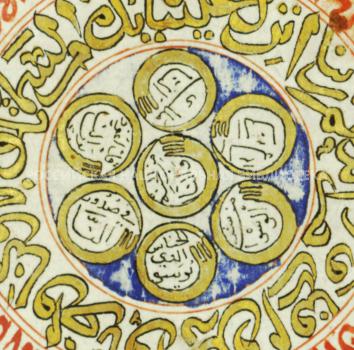

Some portable talismans comprise the entire text of the Quran or selected long chapters, frequently accompanied by prayers believed to be efficacious. From the 14th century onwards, there are known long narrow scrolls on which the Quranic text, written in extremely minute Ghubar script, forms decorative compositions and pious Quranic phrases. Although difficult to read, these manuscripts were thought to summon God for assistance to the owner who carries them around.

The National Library of Russia possesses three talismanic scrolls dated from the 15th to18th centuries. Two of them contain only the text of the Quran. The third manuscript, dated 1404, is the oldest and the largest (13–13.5 cm wide and 575 cm long). In addition to surahs, it also includes spell prayers not only in Arabic, but also in Persian and Turkic. One prayer is even composed, probably, in Aramaic, although it is written in the Arabic alphabet. This manuscript (АНС 223) is an outstanding example of Islamic calligraphy and decorative art; it was written in several various scripts by the skillful calligrapher Hasan ibn ‘Abd al–Karim al–Sinubi (i.e. of Sinope).Other scrolls in the collection are miniature in size and date from later times. For instance, a scroll created, probably, in the 18th century has a small missing fragment which was completed with paper at restoration (Кр. 80). The very minute Quranic text forms large calligraphic letters executed in Thuluth script. They constitute one of the best–known verses of the Quran – the Throne Verse (ayat al–kursi, 255th verse of the 2nd surah of the Quran, Al–Baqarah). At the end of the scroll, there is a Persian phrase granting that God protects anyone carrying this bazuband from divas and jinn, as well as from arrows and bullets. The word bazuband means a band 'worn around the upper arm'. That's what people did then, it was customary to wear protective amulets in cases tied around the arm with a strap. The octagonal stone cylinder case was made in the early 19th century.

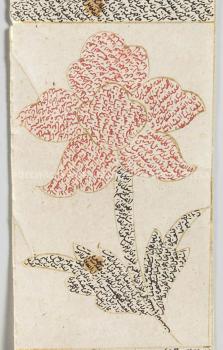

An Ottoman scroll of the 18th century (Dorn 37), features chapters of the Quran, forming not only calligraphic pious Quranic formulas, but also flowers. The scroll is kept in a gold cylinder case with a tughra – the monogram of the Ottoman Sultan Mustafa III (ruled from 1757 to 1773).Another talismanic Qurans present tiny books, round-shaped or octagonal, also written in microscopic Ghubar script. They were also kept in special cases with a cord. A case was usually tied like armbands.

An almost round-shaped Quran that measure 33 mm a diameter impresses with its small size (Дорн 36). The upper board of its lacquer binding, decorated with flowers, has survived. Such bindings are typical of the Iranian art of the late 18th–19th centuries. The miniature Quran is housed within an octagonal silver case with a lug through which a green cord passes.

Small octagonal manuscript books also served as talismans for the army. They were sometimes attached to the shafts of military standards. Meanwhile, an exquisitely ornamented miniature Quran of the 16th – 17th century in a green velvet case (Дорн 35) could well have been intended for personal use.

Quranic Texts in Muraqqa Albums

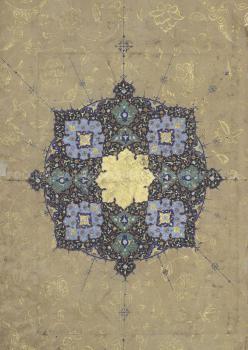

A muraqqa is an album in book form, containing samples of calligraphy and miniature paintings. A book – album first appeared in the 16th century in Iran. The name for such a manuscript means in Persian ‘patched together’. Pieces from different sources and times were mounted on album pages, with new decorative borders being added. The finest albums, assembled at courts of the ruling persons, were elaborately decorated and were composed of true artworks.

Many samples of calligraphy were created by contemporary master calligraphers as separate leaves. If the scribe was skilled and had a good reputation, such leaves became an important source of income for him. In addition to contemporary pages, albums sometimes contain fragments from the works of past.The majority of calligraphy specimens in these albums are poems by popular authors, famous sayings, proverbs, sometimes prayers. Quranic verses are also not infrequent among them. They were mounted both on pages specially created for albums, and on those that were removed from earlier manuscripts.

The National Library of Russia houses three muraqqa albums which contain calligraphy specimens with fragments of the Quranic text. One of the album pages (Дорн 147, fol. 34v) contains two fragments removed from an original manuscript, obviously owing to errors made by a calligrapher copying the sacred text.

Two fragments from one copy of the Quran are found in two different albums (Дорн 147, fol. 2 and Дорн 148, fol. 24). At the same time, one of the fragments has greatly changed its original appearance because of illumination that was added between lines when assembling the muraqqa.

Finally, one of the album pages (Дорн 148, fol. 57) is made up of several words cut out of a very large manuscript and pasted onto this folio. The letters are 8–9 cm tall. Such huge manuscripts, written in Muhaqqaq or Thuluth, were popular in the 15th century. Legend says that the most famous large–format Quran was created by the Timurid prince Baysunghur Mirza (1397–1433), a celebrated book lover, philanthropist and calligrapher. But modern researchers tend to think that it is penned by calligrapher Umar al–Aqta who worked, among others, for Timur, Emir of the Timurid Empire. Separate leaves of this Quran are now split between different museums and private collections around the world. Copied in beautiful Muhaqqaq script, the manuscript measures about 112 x 179 cm; each page contains only seven lines of text. The calligraphy of excerpts on the album page is extremely similar to the writing style in the Baysunghur Quran, but the letters are roughly twice as small as that.

Most of the Quranic calligraphy presented in the albums of the NLR is executed in Muhaqqaq and Naskh scripts. The exceptions are leaves containing Chapter 1 (Surah al–Fatiha), written in Nastaʿliq script by the famous Iranian master calligraphers Mir ʿImad al–Hasani (died 1615) and his disciple ʿAbd ar–Rashid, (Дорн 489, fols. 1v-2, Дорн 489, fols. 9v-10).

O. Vasilieva, O. Yastrebova