The Netherlands - a small country in northern Europe, has made a significant contribution to the history of the world's material and spiritual culture. Dutch painting is widely known. The history of European civilization can not be imagined without the Dutch publishing, philosophy, science, philology, etc.

Witnesses of the past stored in the National Library of Russia - handwritten books and documents from the 15th-19th centuries show the deep layers of the Dutch culture and help to understand better the centuries-old political and cultural relations between Russia and the Netherlands.

¬ęModern Devotion¬Ľ (Devotio moderna)

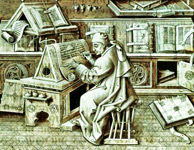

The religious movement ¬ęModern Devotion¬Ľ (Devotio moderna) began in the late fourteenth-century in the north of the Netherlands. It gave a tremendous impact on the religious and cultural life of the Low Countries and Germany. The movement joined two organizational structures: the communities of of the brothers of the common life, who lived as monks but did not take vows, and monasteries of Augustinian Canons at Windesheim (near Zwolle, Holland). Windesheim became the center of the movement. The ¬ęModern Devotion¬Ľ called for living as the first Christians in the early Church did and for developing a deeply personal, conscious attitude towards the Christian faith, following the example of Jesus. Renewal occured through books written in the scriptorium of the ¬ęModern Devotion¬Ľ: among them were Bybles both in Latin and in the vernacular, religious literature comprehensible for middle of the clergy and literate citizens, devotional works and Books of Hours in the vernacular.The National Library possesses manuscripts from libraries of the ¬ęModern Devotion¬Ľ. For instance, the origins of the treatise On the Spiritual Ascents (De spiritualibus ascensionibus), written by Gerard Zerbolt (1367-1398), the first librarian of the Brothren of the Common Life, go back to the Bethlehem Monastery in Louvain.

In his another essay entitled On German Books (De libris teuthonicalibus), Zerbolt developed the idea that all nations, including the Dutch, had the right to read the Bible in their own language. The main monastery of the ¬ęModern Devotion¬Ľ at Windesheim had two libraries: one contained Latin books for the monks, the other held books in the vernacular for the lay brothers. The Dutch books library was in charge of Canon Jan Scutken (+1423).Putting Zerbolt's ideas into practice, he translated into Dutch all the books of the New Testament and read them to the laity during monastic meal. The National Library of Russia keeps two manuscript Gospels in translation made by Jan Skutken. They belonged to nunneries of the Congregation of Windesheim: the Convent of Saint Agnes in the village of Neerbosch near Nijmegen and the Convent of Saint Agnes in Haarlem. The latter carries a record attesting to the accuracy of the translation of Jan Scutken, 'There ends the Gospel of St. Matthew in Dutch, which was very accurately translated from Latin'.

At the end of the book there are two inscriptions: the scrib's colophon giving the date of rewriting(1476), and the owner's record of the Convent of Saint Agnes in Haarlem.

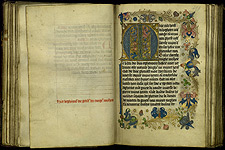

The most popular books during the fifteenth century were Books of Hours. These were prayer books which private persons used to pray in the canonical hours, like the monks. Researchers call them bestsellers of the late Middle Ages. Many Books of Hours were decorated with miniatures with scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin.Originally Books of Hours were in Latin, then Book of Hours in the vernacular appeared.

The founder of the ¬ęModern Devotion¬Ľ movement Geert Groote (1340-1384) translated the Latin text into the Dutch, and our library keeps a parchment copy of Groote's Book of Hours, created in the fifteenth century.The origins of the seventeenth century Dutch Golden Age lie in the Middle Ages. It is well known that Dutch universities were the best in Europe, but it is also worth emphasizing that in the Netherlands there were many more people who could read and write, than in any other country. The need for a national system of public education was generally recognized in the Netherlands already in the eighteenth century.

In his didactic poems, the father of Dutch literature Jacob van Maerlant († 1300) called to establish city schools accessible to each child. In the early fifteenth century, Denis the Carthusian († 1471) wrote that every parish should have a school to teach children Latin, so they would be able to understand the Mass, to read and sing in church. At the time of Groote' friend, the innovator in education Johannes Cele († 1417), 1,200 students studied in the municipal school of Zwolle, 2200 boys - in the school of Deventer. Many boys from northern Germany were taught in schools of Zwolle, Deventer and other Dutch cities. It was considered a holy deed to take a student to a family and give him bread, beer and bed. One of these students was Thomas from the German city of Kempen. After leaving school in Deventer, he entered the Monastery of Mount St. Agnes at Agnetenberg near Zwolle, which was part of the Congregation of Windesheim.