Middle Ages

The Middle Ages have a special place in the history of Europe. During this period, a Christian community was formed in Europe. It laid the foundations of modern sciences and an education system. Established in the Middle Ages, national states and institutions promoted the further development of Western civilization.

Despite its many-sidedness, spirituality and culture of the Middle Ages were built around a single vector. The religion permeates all spheres of life of the medieval society. Stored in the NLR, medieval literary landmarks cover the period from the 5th to the early 16th centuries. They make it possible to trace the stages of the thousand-year evolution of Western Christianity from the conversion of the Germanic barbarian tribes to Christianity up to the Reformation of the 16th century, when the Western Church was divided into into Catholic and Protestant groups.

Making of the Christian Doctrine

The doctrine of Western Christianity was developed in the 2nd-5th centuries and was fully formed in the works of the four Fathers of the Church – Sts. Ambrose (340-397), Augustine (354-430), Jerome (342-419/420) and Pope Gregory I the Great (540-604).

The doctrine of Western Christianity was developed in the 2nd-5th centuries and was fully formed in the works of the four Fathers of the Church – Sts. Ambrose (340-397), Augustine (354-430), Jerome (342-419/420) and Pope Gregory I the Great (540-604).

One of the main treasures of the National Library of Russia is a lifetime collection of Augustine's writings, created in the city of Hippo in North Africa, home to St. Augustine, there he became bishop. The book contains the earliest known copy of the main Augustine's work “On Christian Doctrine”.

At the beginning of the 5th century, Saint Jerome completed the work of his life – translation of the Bible into Latin. The Old Testament was translated by Jerome from the Hebrew language, the New Testament – from Greek. The Western Church has received the best-known Latin translation that, after a millennium, at the Council of Trent in 1546, was recognized as a standard translation of the Catholic Church, with the name the Vulgate (in Latin the Biblia Vulgata is "Common Bible"). Since the 7th century, almost all the books of the Bible in Europe corresponded to Jerome's translation. Jerome did not confined himself to translating the St. Scripture. Like other Church Fathers, he wrote comments on the Bible, which contributed to the development of the doctrine of the Catholic Church.

Carolingian Renaissance

The Roman statesman and writer Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585) was the creator of a new, Christian paradigm of culture. In his southern Italian estate, Cassiodorus founded a monastery. The monastery had a large library, a school and a scriptorium – a workshop where manuscripts were copied. The library consisted of works of classical Latin and late Roman Christian literature. In the school, puples learnt to read, write and do translations from Greek into Latin.

Cassiodorus expounded his Christian education programme in the book “On the Soul”. He set the task to preserve the best examples of Roman culture and to integrate them into the Christian system of values. Cassiodorus considered intellectual work to be the principal element of the emerging Christian culture. These ideas, as well as the art of copying books were adopted by the monastic Order of St. Benedict (about 480-547). In the Early Middle Ages, Benedictine monasteries became centers of conservation of book knowledge and education. The exhibition shows a codex with Jerome's commentary on the biblical “Book of Numbers”, rewritten in the Cassiodorus Monastery.European culture has been shaped by Roman and barbarian traditions. Their integration initiated by Cassiodorus, was completed in the period of the so called Carolingian Renaissance (8th-9th centuries). It was the first time of the flowering of culture after the barbarian invasions that caused the fall of the Roman Empire.

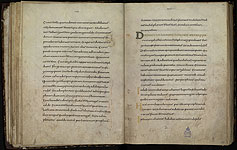

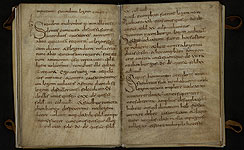

For example, the manuscript treatise “Rectractationes” (an English translation of the Latin title is "Retractations") was created by St. Augustine during the 8th century in one of the centers of the Carolingian Renaissance, the Abbey of Corbie. The composition includes revisions and edits that Augustine found it necessary to add to his works in his later years. The codex was produced in the famous Corbie Abbey, in which scriptorium the uniform script known as Carolingian minuscule was developed as a European calligraphic standard.

For example, the manuscript treatise “Rectractationes” (an English translation of the Latin title is "Retractations") was created by St. Augustine during the 8th century in one of the centers of the Carolingian Renaissance, the Abbey of Corbie. The composition includes revisions and edits that Augustine found it necessary to add to his works in his later years. The codex was produced in the famous Corbie Abbey, in which scriptorium the uniform script known as Carolingian minuscule was developed as a European calligraphic standard.

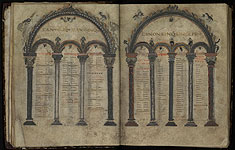

Carolingian Renaissance has affected all areas of the Empire of Charlemagne (742/748-814). King Charles established uniform laws and worship to control the conquered areas, and he began with the unification of the liturgy. To this effect, the Anglo-Saxon Alcuin (ca. 735 - 804), Emperor's Advisor on religious and cultural issues, made the revision of St. Jerome's Latin translation of the Bible. Alcuin was abbot of the St. Martin's monastery in Tours where he organized very intensive production of Bibles. The National Library of Russia possesses the Gospel created in Tours. The book is adorned with canons tables and the opening words of the prologues, written out in gold and silver ink on purple ribbons.

Carolingian Renaissance has affected all areas of the Empire of Charlemagne (742/748-814). King Charles established uniform laws and worship to control the conquered areas, and he began with the unification of the liturgy. To this effect, the Anglo-Saxon Alcuin (ca. 735 - 804), Emperor's Advisor on religious and cultural issues, made the revision of St. Jerome's Latin translation of the Bible. Alcuin was abbot of the St. Martin's monastery in Tours where he organized very intensive production of Bibles. The National Library of Russia possesses the Gospel created in Tours. The book is adorned with canons tables and the opening words of the prologues, written out in gold and silver ink on purple ribbons.

The text of the Gospel is written in Carolingian minuscule that is easy to write and clear to read. In the 15th century, Italian humanists sought for manuscripts of Roman authors in monasteries and found antique works copied in Carolingian minuscule. For humanists, clarity and simplicity of Carolingian minuscule associated with the classic heritage. As humanists mistook Carolingian minuscule for script of Ancient Rome, they began to write in this hand. So a new type of writing emerged – a round humanist script from which the modern Latin book font is derived.

The text of the Gospel is written in Carolingian minuscule that is easy to write and clear to read. In the 15th century, Italian humanists sought for manuscripts of Roman authors in monasteries and found antique works copied in Carolingian minuscule. For humanists, clarity and simplicity of Carolingian minuscule associated with the classic heritage. As humanists mistook Carolingian minuscule for script of Ancient Rome, they began to write in this hand. So a new type of writing emerged – a round humanist script from which the modern Latin book font is derived.

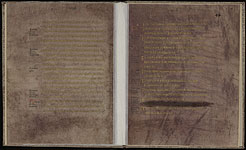

At the court of Charlemagne, there were produced Gospels written in gold and silver ink on purple dyed parchment. Books, copied in the court scriptorium, were intended for kings, cathedrals and monasteries. There has survived a poem of the scribe Godescalc who transcribed books for Charlemagne, 'Gold letters on purple sheets promise the kingdom of heaven and heavenly joy through the shedding of red blood'. The National Library of Russia stores 4 leaf from the purple Gospel of Matthew written in gold ink, which headers and notes in the fields are executed in silver ink. The manuscript was created in the Palatine School of Charlemagne in Aachen.

At the court of Charlemagne, there were produced Gospels written in gold and silver ink on purple dyed parchment. Books, copied in the court scriptorium, were intended for kings, cathedrals and monasteries. There has survived a poem of the scribe Godescalc who transcribed books for Charlemagne, 'Gold letters on purple sheets promise the kingdom of heaven and heavenly joy through the shedding of red blood'. The National Library of Russia stores 4 leaf from the purple Gospel of Matthew written in gold ink, which headers and notes in the fields are executed in silver ink. The manuscript was created in the Palatine School of Charlemagne in Aachen.

Nota bene: the gold ink in parchment manuscripts remains brilliat, the silver one has darkened and has begun to eat through parchment over time. That explains why texts written in silver ink are dull.

The tradition of producing purple Gospels continued after the death of Charlemagne. In the 9th century, the luxurious Four Gospels, written in gold and silver ink, was created in Autun.

The tradition of producing purple Gospels continued after the death of Charlemagne. In the 9th century, the luxurious Four Gospels, written in gold and silver ink, was created in Autun.

High Middle Ages

By the end of 12th century, an economic and political role of European cities increased, this was reflected in the construction of monumental cathedrals in the Gothic style replacing Romanesque.

In European cultural centers such as Bologna, Montpellier, Paris, Oxford, ealiest European universities appeared. These private corporations of teachers and students formed a new type of stage-by-stage learning, unknown to the ancient world. At the preparatory faculty - the Faculty of Arts ( artes liberales in Latin), students experienced two courses of studies. In the first stage (the trivium), they studied Latin grammar to gain linguistic analysis skills, rhetoric to obtain the ability to express thoughts, and logic - the art of reasoning and dialogue. The second course (the quadrivium) involved the study of arithmetic (the science of numbers and computations), geometry (including the "Elements" of Euclid and natural science), music (the study of world harmony) and astronomy (the knowledge of the structure of the heavens). Next, a student was admitted to one of the higher faculties: of theology, law, or medicine.

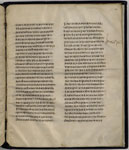

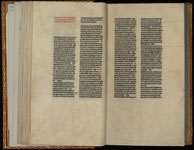

The Theological Faculty at the University of Paris was recognized as the leader in matters of faith. No coincidence that in the early thirteenth century, the Paris theologians undertook work on the standardization of the Bible. They took Alcuin's corrected Vulgate as a basis. In the Bibles created before the 13th century, the number and order of the biblical books differed: researchers account for more than two hundred variants. Today's familiar order of the biblical books became fixed in the 13th century when the so-called Paris Bibles appeared. The number of prefaces has been reduced: out of more than 500, Parisian theologians have left 64 St. Jerome's Prefaces. The books of St. Scriptures were divided into chapters and were provided with headings. Alphabetical lists of biblical characters with brief comments were given at the end.

The term Paris Bibles refers to the single-volume Bibles of small size. These portable books were written in tiny Gothic script on pages of very thin parchment. To have such a complete but small Bible was a great advantage so they became widespread. Before the thirteenth century, Bibles were typically produced in multiple volumes, the full text Bibles were relatively rare, pandects - large Bibles complete in one volume - occurred even rarer. Separate books, especially the Psalms and the Gospels, also continued to be copied. The Paris pandects gave scholars and students an opportunity to buy complete Bibles at a reasonable price. It was not cheap but less expensive then before. These books make it easier to study the Bible, because they contain scientific, in the modern sense of the word, aids: a table of contents and an annotated index of names.

The term Paris Bibles refers to the single-volume Bibles of small size. These portable books were written in tiny Gothic script on pages of very thin parchment. To have such a complete but small Bible was a great advantage so they became widespread. Before the thirteenth century, Bibles were typically produced in multiple volumes, the full text Bibles were relatively rare, pandects - large Bibles complete in one volume - occurred even rarer. Separate books, especially the Psalms and the Gospels, also continued to be copied. The Paris pandects gave scholars and students an opportunity to buy complete Bibles at a reasonable price. It was not cheap but less expensive then before. These books make it easier to study the Bible, because they contain scientific, in the modern sense of the word, aids: a table of contents and an annotated index of names.

The Paris Bibles were also indispensable to mendicant orders founded in the early 13th century: the Order of St. Francis and the Order of St. Dominica. The monks of the orders were granted the right to preach and to perform the sacraments. A small volume took up little space in a monastic pouch, and its reference system helped to easily find a desired text for sermons.

The bulls, issued by Pope Alexander IV (1185-1261), evidence that he was Protector of the Order of Franciscans. A papal bull is a particularly important message from the Holy See. It is named after the lead seal (bulla) that was hunged to the end of the document in order to authenticate it. It showed the name of the reigning Pope on one side, and portrayed the heads of the Apostles Peter and Paul on the other. All papal letters start with strictly regulated introduction. The name of the Pope (in the bull on March 23, 1261, it is Alexander IV) is followed by the formula, 'Alexander, Bishop, servant of the servants of God' ("Alexander episcopus servus servorum Dei"). In his message, Alexander IV entrusted the Franciscan monks to the Archbishop of Cologne, in order that all religious and secular institutions, as well as religious and secular people of the archdiocese would provide all possible assistance to the Franciscan monks for brotherly love.

The bulls, issued by Pope Alexander IV (1185-1261), evidence that he was Protector of the Order of Franciscans. A papal bull is a particularly important message from the Holy See. It is named after the lead seal (bulla) that was hunged to the end of the document in order to authenticate it. It showed the name of the reigning Pope on one side, and portrayed the heads of the Apostles Peter and Paul on the other. All papal letters start with strictly regulated introduction. The name of the Pope (in the bull on March 23, 1261, it is Alexander IV) is followed by the formula, 'Alexander, Bishop, servant of the servants of God' ("Alexander episcopus servus servorum Dei"). In his message, Alexander IV entrusted the Franciscan monks to the Archbishop of Cologne, in order that all religious and secular institutions, as well as religious and secular people of the archdiocese would provide all possible assistance to the Franciscan monks for brotherly love.

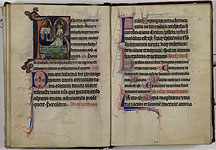

The Gothic style dominated the architecture and sculpture of Western Europe during the high medieval period. The style also extended to small arts, which included calligraphy and book illumination. The National Library of Russia holds one of the finest examples of French Gothic book art – a Missal created in the late 13th century in Paris for the Abbey of St. Nicaise in Reims. A Missal is a liturgical book containing all texts necessary for the Catholic worship. The Reims Missal is notable for its rich ornamental decoration and perfectly executed miniatures. 18 out of the 20 full leaf miniatures were created after the treatise of Jean de Joinville (1223-1317) “Credo”, written by Joinville during the Seventh Crusade to comfort and strengthen the faith of the sick and dying Crusaders in Palestine.

The Gothic style dominated the architecture and sculpture of Western Europe during the high medieval period. The style also extended to small arts, which included calligraphy and book illumination. The National Library of Russia holds one of the finest examples of French Gothic book art – a Missal created in the late 13th century in Paris for the Abbey of St. Nicaise in Reims. A Missal is a liturgical book containing all texts necessary for the Catholic worship. The Reims Missal is notable for its rich ornamental decoration and perfectly executed miniatures. 18 out of the 20 full leaf miniatures were created after the treatise of Jean de Joinville (1223-1317) “Credo”, written by Joinville during the Seventh Crusade to comfort and strengthen the faith of the sick and dying Crusaders in Palestine.

The Middle Ages laid the foundations of European law. This process culminated in the next historical period, in the Modern Times, but it was in the Middle Ages when the contours of the contemporary national legal systems of Europe became shaped. They are generally based on common law. The NLR maintains a copy of the most famous landmark of law, dated to the early Middle Ages, the so-called “Salic truth” – the customary law code of the Salian Franks. The Germanic tribes of the Franks, inhabited the territory of modern France, followed this recorded guidelines during the 7th-9th centuries.

The Middle Ages laid the foundations of European law. This process culminated in the next historical period, in the Modern Times, but it was in the Middle Ages when the contours of the contemporary national legal systems of Europe became shaped. They are generally based on common law. The NLR maintains a copy of the most famous landmark of law, dated to the early Middle Ages, the so-called “Salic truth” – the customary law code of the Salian Franks. The Germanic tribes of the Franks, inhabited the territory of modern France, followed this recorded guidelines during the 7th-9th centuries.

The transition from tribal to feudal legal practices took place from the 12th to 14th centuries. The Romano-Germanic law system was grown out of the study of Roman law which was based on the right of private property and commodity-money relations. Reception of Roman Law began with its interpretation by university lawyers ("legal glossators") and ended with the inclusion of abstract rules in the legal codes of European states. At universities, Roman law was taught on the basis of Emperor Justinian's Law Code (483-565).

The transition from tribal to feudal legal practices took place from the 12th to 14th centuries. The Romano-Germanic law system was grown out of the study of Roman law which was based on the right of private property and commodity-money relations. Reception of Roman Law began with its interpretation by university lawyers ("legal glossators") and ended with the inclusion of abstract rules in the legal codes of European states. At universities, Roman law was taught on the basis of Emperor Justinian's Law Code (483-565).

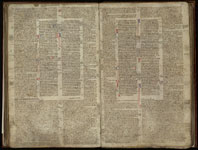

In the Middle Ages, the church served a variety of functions, which later became state-owned. For the formation of a pan-European legal culture, the canon (Church) law was of great importance. It was studied at universities on a par with the Roman civil law. The universal and extraterritorial canon law did not know national boundaries, all European countries obeyed its regulations. The canon law was based on Roman law and represented the system of the canons – the rules relating to the church order itself, and to the social life of believers (marriage, will and so on.).

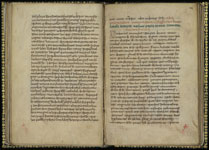

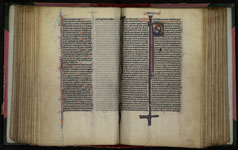

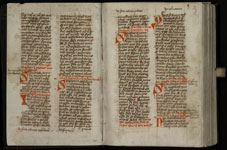

This effective legal system is operated through the broadest jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts dealing with matters of spiritual and secular life. One of the most significant monuments of canon law is a collection of papal decretals with glosses (comments). The collection was compiled in 1234 on the orders of Pope Gregory IX (c. 1145 -1241). The decretals are written in two columns in the center, their individual chapters are marked by large red and blue initials. Glosses are written in a smaller hand on the fields and under the lines of decretals.

In the Middle Ages, the church served a variety of functions, which later became state-owned. For the formation of a pan-European legal culture, the canon (Church) law was of great importance. It was studied at universities on a par with the Roman civil law. The universal and extraterritorial canon law did not know national boundaries, all European countries obeyed its regulations. The canon law was based on Roman law and represented the system of the canons – the rules relating to the church order itself, and to the social life of believers (marriage, will and so on.).

This effective legal system is operated through the broadest jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts dealing with matters of spiritual and secular life. One of the most significant monuments of canon law is a collection of papal decretals with glosses (comments). The collection was compiled in 1234 on the orders of Pope Gregory IX (c. 1145 -1241). The decretals are written in two columns in the center, their individual chapters are marked by large red and blue initials. Glosses are written in a smaller hand on the fields and under the lines of decretals.

A city law played a special role in the development of the pan-European legal culture. Its regulations were recorded in city statutes. Municipal law is not a feudal right, it lay the foundation of the future bourgeois law. One of the most well-known systems of a city right exists at Magdeburg (Central Germany) in the 13th century. Legal norms of the Magdeburg Law regulated the life in the city: assigned the organization of craft production, trade, the order of election and activities of the city government, guild associations of artisans and merchants.

A city law played a special role in the development of the pan-European legal culture. Its regulations were recorded in city statutes. Municipal law is not a feudal right, it lay the foundation of the future bourgeois law. One of the most well-known systems of a city right exists at Magdeburg (Central Germany) in the 13th century. Legal norms of the Magdeburg Law regulated the life in the city: assigned the organization of craft production, trade, the order of election and activities of the city government, guild associations of artisans and merchants.

Late Middle Ages. Renaissance

The Late Middle Ages (14th - 15th cc.) are often considered to be a period of transition of European civilization from the medieval to modern times. It saw the growth of secular trends, the turn for the ancient cultural heritage and humanistic world view. Do not, however, equate the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, since the concept of the Renaissance implies changes in the sphere of culture, rather than throughout the whole complex of political and spiritual life of the European countries. It should also borne in mind that the time frame of the Renaissance varied between different regions of Europe within one or one and a half centuries.

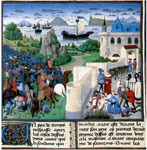

The Grand French Chronicles (“Les Grandes Chroniques de France”), or, as it is called, “The Chronicles of St. Denis”, describes the history of the French kings from their origins in Troy to the late 14th century. In contrast to the French local chronicles, the Grand French Chronicles reflects the history of the entire kingdom, which was of great importance for the formation of the cultural unity of the French nation.

Approximately 130 copies of the "Grandes Chroniques de France" have survived up to now. The Petersburg copy is written on request of the bishop of Tula Guillaume Fillastre,(† 1473), Chancellor of the Order of the Golden Fleece founded by Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy. For the period before 1226, the Petersburg manuscript repeats the version of the royal Grandes Chroniques de France produced for King Charles V. After this date, it contains material from the chronicles of the pro-Burgundian orientation. Guided by the interests of Burgundy, Fillastre sought to justify the political claims of the powerful Duke Philip the Good, a formally vassal of the French king Louis XI, to be an independent ruler of his own kingdom.

The manuscript is beautifully illuminated. This luxurious volume contains 25 large miniature paintings and 65 smaller miniatures executed by three artists. One of them was the outstanding artist of the age, Simon Marmion (ca. 1425 -1489), whom his contemporaries called the Prince of Miniaturists. The book opens with a scene of the presentation of the 'Grandes Chroniques de France' to Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good. This event took place on 1 January 1456, or 1457. Abbot Guillaume Fillastre in episcopal miter and with crosier, gives a book to the Duke Philip the Good as a present. To the right of the Duke are his sons: the heir, the future Duke of Burgundy Charles the Bold, and the illegitimate son Antoine whom contemporaries nicknamed the Great Bastard of Burgundy. The members of the ducal family wear the Chains of the Order of the Golden Fleece around their necks. A clock worked by weights hangs on the wall of the hall. A mechanical clocks, with one hand, were only on the towers of the city's cathedral. A home clock were a rarity, and only very wealthy people could purchase them.

The manuscript is beautifully illuminated. This luxurious volume contains 25 large miniature paintings and 65 smaller miniatures executed by three artists. One of them was the outstanding artist of the age, Simon Marmion (ca. 1425 -1489), whom his contemporaries called the Prince of Miniaturists. The book opens with a scene of the presentation of the 'Grandes Chroniques de France' to Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good. This event took place on 1 January 1456, or 1457. Abbot Guillaume Fillastre in episcopal miter and with crosier, gives a book to the Duke Philip the Good as a present. To the right of the Duke are his sons: the heir, the future Duke of Burgundy Charles the Bold, and the illegitimate son Antoine whom contemporaries nicknamed the Great Bastard of Burgundy. The members of the ducal family wear the Chains of the Order of the Golden Fleece around their necks. A clock worked by weights hangs on the wall of the hall. A mechanical clocks, with one hand, were only on the towers of the city's cathedral. A home clock were a rarity, and only very wealthy people could purchase them.

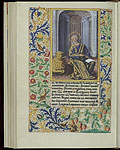

Books of hours (breviary, horae, livres d'heurs, Stundenbücher) became the most read books of 14th-15th centuries. Researchers call them bestsellers of the late Middle Ages. The name is derived from the seven daily prayer services (hours) in the church, prescribed by monastic rules. To understand the phenomenon of books of hours, we should go back to the 12th century. The monastic mystics in their writings trended towards individualization of the religious life. The Benedictine Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux (1091-1153) in his works emphasized compassion on the human suffering of Christ and the Virgin. He saw the ideal of the Christian life in imitation of Christ's earthly path (imitatio Christi), the Virgin Mary was glorified not only as the Queen of Heaven, but as a rejoicing and suffering mother. Pious works in Latin and national languages appeared, which simply and clearly told about the evangelical events and the mystery of salvation. Books of hours were produced for the laity. They organically agreed with a new, personal attitude of believers towards the truths of the Christian faith, and determined the structure of devotion during 14th-15th centuries. Lay people were able to pray at the canonical hours, as monks. The main part of the Liturgy of the Hours - the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary is divided into 7 canonical hours. The prayers devoted to the Mother of God could be followed by the Scripture Readings, other services, prayers to the saints and the hymns. The nobles possessed the books of hours decorated with luxurious borders and magnificent miniatures executed by the best artists of Europe. The National Library of Russia keeps books of hours, belonged to the Duke of Orleans, the future King of France Louis XII (1462-1515), and Queen Mary Syuart of Scotland (1542-1587).

At the end of 15th century, a book miniature becomes an independent work of art with its own ideological and aesthetic programme. One of the miniatures in the book of Louis d'Orleans depicted a genre scene. Evangelist Luke paints reverently the image of the Virgin Mary who sits for her portrait as a pious citizen in her familiar home surroundings. The next page shows St. Jerome in his cell, a lion makes himself comfortable next to him.

At the end of 15th century, a book miniature becomes an independent work of art with its own ideological and aesthetic programme. One of the miniatures in the book of Louis d'Orleans depicted a genre scene. Evangelist Luke paints reverently the image of the Virgin Mary who sits for her portrait as a pious citizen in her familiar home surroundings. The next page shows St. Jerome in his cell, a lion makes himself comfortable next to him.

These two miniatures are not only perfectly executed, they are also interested as samples of the so-called Holy Tradition. Christianity is the religion of divine revelation, based on texts of the Holy Scripture. But in the minds of medieval people, the Holy Tradition always was close to the Holy Scripture.

According to the Books of the New Testament (a preface of St. Jerome to the Gospel of Luke), St. Luke was a doctor. Without denying this, the Holy Tradition ascribes a talent of the painter to St. Luke and credits him with having made a portrait from life of the Virgin Mary with Child. For this reason, the painters' guilds throughout Europe had the name of St. Luke.

These two miniatures are not only perfectly executed, they are also interested as samples of the so-called Holy Tradition. Christianity is the religion of divine revelation, based on texts of the Holy Scripture. But in the minds of medieval people, the Holy Tradition always was close to the Holy Scripture.

According to the Books of the New Testament (a preface of St. Jerome to the Gospel of Luke), St. Luke was a doctor. Without denying this, the Holy Tradition ascribes a talent of the painter to St. Luke and credits him with having made a portrait from life of the Virgin Mary with Child. For this reason, the painters' guilds throughout Europe had the name of St. Luke.

There was such a legend. When the translator of the Bible into Latin St. Jerome lived in a cloister, a lame lion came to this monastery. The monks fled in terror, but Jerome examined the sick animal's paw and removed a splinter out of it. Then, a grateful lion became his constant companion. In the artistic terms, both miniatures are designed as small easel paintings.

In France, during the late 15th centuty, elements of Renaissance just emerged. As for Italy, the country entered the era of the Renaissance already in the second half of the fourteenth century. The first Italian humanist Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374) revived the science of man - studia humanitatis (Cicero's term). Humanists believed that eternal truths are hiden under the cover of poetic invention of ancient literature. They rejected scholastic knowledge and assigned primary importance to ethics, the science of the formation of the human person, based on thoughtful reading Roman authors, with their ideal of human dignity. The defining feature of Italian humanism was proficiency in the classical, in contrast to the medieval, Latin language. Contemporaries appreciated Petrarch for treatises on history and ethics, written in fine classical Latin. Petrarch learnt norms of elegant Latin from Cicero, whose works he tirelessly sought for in monastic libraries. For his Latin works, Petrarch was crowned in 1341 in Rome with a laurel wreath. The National Library of Russia stores a parchment manuscript with one of the most famous Latin treatises of Petrarch “Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul” (De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae). The book contains the four half-length portrait of Petrarch, having unquestionable resemblance to his authentic images.

In France, during the late 15th centuty, elements of Renaissance just emerged. As for Italy, the country entered the era of the Renaissance already in the second half of the fourteenth century. The first Italian humanist Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374) revived the science of man - studia humanitatis (Cicero's term). Humanists believed that eternal truths are hiden under the cover of poetic invention of ancient literature. They rejected scholastic knowledge and assigned primary importance to ethics, the science of the formation of the human person, based on thoughtful reading Roman authors, with their ideal of human dignity. The defining feature of Italian humanism was proficiency in the classical, in contrast to the medieval, Latin language. Contemporaries appreciated Petrarch for treatises on history and ethics, written in fine classical Latin. Petrarch learnt norms of elegant Latin from Cicero, whose works he tirelessly sought for in monastic libraries. For his Latin works, Petrarch was crowned in 1341 in Rome with a laurel wreath. The National Library of Russia stores a parchment manuscript with one of the most famous Latin treatises of Petrarch “Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul” (De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae). The book contains the four half-length portrait of Petrarch, having unquestionable resemblance to his authentic images.

Petrarch became a classic of world literature thanks to the sonnets and canzones in the Italian language, dedicated to Donna Laura. However, he called them nothing more than gauds intended to reduce his heartache. But perhaps, it was the classic Latin "science of man" that gave Petrarch the opportunity to liberate the heart and allowed him to freely express his feelings. The magnificent Renaissance manuscript containing poetic works of Petrarch was created in Florence.

Petrarch became a classic of world literature thanks to the sonnets and canzones in the Italian language, dedicated to Donna Laura. However, he called them nothing more than gauds intended to reduce his heartache. But perhaps, it was the classic Latin "science of man" that gave Petrarch the opportunity to liberate the heart and allowed him to freely express his feelings. The magnificent Renaissance manuscript containing poetic works of Petrarch was created in Florence.

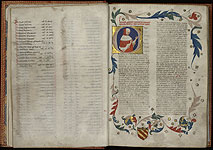

Another Italian codex with the text of one of the early works of Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) is no less brilliant. The plot of the novel "Filokolo" is based on the stories from medieval romances. The first leaf of the manuscript is gilded. There is a fantastic portrait of Boccaccio with a laurel wreath on his head, painted within the historiated initial "M". The richness of the ornamental motifs on the sheet perfectly matches the classic elegance of a renaissance frame.

Another Italian codex with the text of one of the early works of Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) is no less brilliant. The plot of the novel "Filokolo" is based on the stories from medieval romances. The first leaf of the manuscript is gilded. There is a fantastic portrait of Boccaccio with a laurel wreath on his head, painted within the historiated initial "M". The richness of the ornamental motifs on the sheet perfectly matches the classic elegance of a renaissance frame.

In addition to hand written books, the National Library holds diplomatic documents, letters of politicians, scientists, writers.

Contemporaries called the most important representative of the Northern Renaissance, a native of the Netherlands, Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469-1536), "the prince of humanists". Erasmus occupied a very special place in the circle of the intellectuals, he also held the unprecedentedly honorable and influential position in society. In his person, a man of science and literature achieved such an high status in society for the first time in European history. In a letter to the French theologian Henri Botte, Erasmus tells the sad news about the death of his friend and publisher of his works Johann Froben (1460-1527). For many years, the Basel humanist, scholar and printer Johann Froben maintained a very close friendship with Erasmus and published his works. Visiting Basel, Erasmus stayed in Froben's house and took an active part in the publication of his own works. In a letter to Botte, Erasmus writes about bitterness over the loss of a friend and appreciates greatly Froben's human and professional qualities.

In a letter to the French theologian Henri Botte, Erasmus tells the sad news about the death of his friend and publisher of his works Johann Froben (1460-1527). For many years, the Basel humanist, scholar and printer Johann Froben maintained a very close friendship with Erasmus and published his works. Visiting Basel, Erasmus stayed in Froben's house and took an active part in the publication of his own works. In a letter to Botte, Erasmus writes about bitterness over the loss of a friend and appreciates greatly Froben's human and professional qualities.