Pious Literature. Prayer and Books of Houres.

Since the 12th century, the worship of the Virgin Mary took on a major role in the beliefs of the Europeans. In Latin writings of Bernard of Clairvaux, Maria is depicted as a rejoicing and suffering mother. The French Abbot Gautier de Coinci (1177-1236) dedicated to her a poem in French, entitled "The Life and Miracles of Our Lady", with musical interludes on the motives of secular ballads. His work shows the Virgin Mary as a merciful protector of those who sincerely believe in her, and ask her for help. Numerous lives of the saints, designed for a wide range of readers, were copied many times. The most popular was a collection of the 180 stories of the most famous saints "The Golden Legend" by the archbishop of Genoa Jacobus de Voragine (c. 1230-1298), an author of the first Italian translation of the Bible. In his book, Jacobus de Voragine drew on the canonical and apocryphal Gospels, including the Gospel of Nicodemus. Scientists have identified more than 130 texts that was used by him, although most of his readings have no known source.Thus, "The Golden Legend" for the first time calls Mary Magdalene a former loose woman, and assigns names of eastern kings Gaspar, Melchior and Balthazar to the Magi. In "The Golden Legend", miracles co-exist inseparably with reality, so the readers consider wonders which happen thanks to the saints' unwavering faith in God, as part of their everyday life. The book was originally entitled "The Legend of the Saints" («Legenda Sanctorum»), but after Jacobus' death, the next generation of readers called it "The Golden Legend".St. Brigit of Sweden (c. 1303-1373) was descended from a rich noble Swedish family. At the age of 13, she was married, during marriage she bore eight children. After the death of her husband, Brigita started to have visions. She wrote down her visions in Swedish, her confessors translated them into Latin. In 1391, Brigit was canonized, in 1999, Pope John Paul II proclaimed her as a patron saint of Europe.

For the first time, "Visions of St. Brigit" were published in Lübeck in 1472. They were reprinted many times and translated into different languages. The Royal Library of Sweden kept the rough accounts of two revelations in the Swedish language, written by own Brigit's hand. The National Library of Russia possesses a translation of "Visions of St. Brigit" in the Czech language, produced at the early 15th century.Thomas à Kempis (1379 / 80-1471) was the most prominent writer of the Modern Devotion movement. His popular book "The Imitation of Christ" is second to the Bible alone in the number of publications in the Christian world. More than 700 handwritten copies of this book in different languages and 80 early printed books have survived from the fifteenth century. This allows scientists to call "The Imitation of Christ" bestseller of the late Middle Ages. It is interesting that the book aroused the greatest interest in the Ages of Enlightenment and Technological Progress - in the 18th and 20th centuries. Five copies of the "The Imitation of Christ" are held in the National Library of Russia. Written in different regions of Europe, in different languages, in different author’s versions, books have different order of the pieces of text and performed different functions as a part of a collection.

In a prayer book, created in the late fifteenth century in Colone, excerpts from the book "The Imitation of Christ" are arranged so that they formed a brief teaching introduction. The body of prayers is preceded by a few phrases from the first, second and third chapters of the first book of "The Imitation".

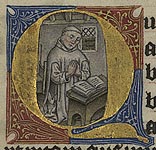

A historiated initial «Q» is decorated with an image of a kneeling monk at prayer.The beautiful painting was performed in the technique of grisaille and creates an atmosphere of reverent silence and concentration. The initial letter preceded the text of "The Imitation"; the text itself, in turn, serves as an introduction to the prayers. Use of excerpts from the "The Imitation of Christ" as a prologue to the prayers is one of the features of the existence of this book in the late Middle Ages.

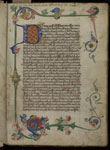

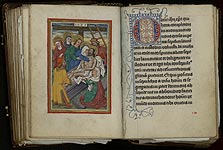

In addition to the Latin text, the manuscript "The Imitation of Christ" has dozens of translations into the main European languages. The National Library of Russia stores handwriteen copies of the book produced in Middle Low German and Dutch at the end of the fifteenth century. IV book of "The Imitation of Christ" in the Middle Dutch was rewritten as anonymous - 'an author is unknown'.Books of hours (breviary, horae, livres d'heurs, Stundenbücher), intended for lay people, became the most read books of 14th-15th centuries. The name is derived from the seven daily prayer services (hours) in the church, prescribed by monastic rules. To understand the phenomenon of books of hours, we should go back to the 12th century. The monastic mystics in their writings trended towards individualization of the religious life. The Benedictine Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux (1091-1153) in his works emphasized compassion on the human suffering of Christ and the Virgin. He saw the ideal of the Christian life in imitation of Christ's earthly path (imitatio Christi), the Virgin Mary was glorified not only as the Queen of Heaven, but as a rejoicing and suffering mother. Pious works in Latin and national languages appeared, they simply and clearly told about the evangelical events and the mystery of salvation. Books of hours organically agreed with a new, personal attitude of believers towards the truths of the Christian faith, and determined the structure of devotion during 14th-15th centuries. Lay people were able to pray at home. The main part of the Liturgy of the Hours - the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary is divided into 7 canonical hours. The prayers devoted to the Mother of God could be followed by the Scripture Readings, other services, prayers to the saints and the hymns

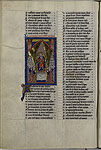

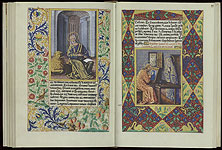

At the end of 15th century, a book miniature becomes an independent work of art with its own ideological and aesthetic programme. One of the miniatures in the book of Louis d'Orleans, the future King of France Louis XIV, depicted a genre scene. Evangelist Luke paints reverently the image of the Virgin Mary who sits for her portrait as a pious citizen in her familiar home surroundings. The next page shows St. Jerome in his cell, a lion makes himself comfortable next to him.

These two miniatures are not only perfectly executed, they are also interested as samples of the so-called Holy Tradition. Christianity is the religion of divine revelation, based on texts of the Holy Scripture. But in the minds of medieval people, the Holy Tradition always was close to the Holy Scripture. According to the Books of the New Testament (a preface of St. Jerome to the Gospel of Luke), St. Luke was a doctor. Without denying this, the Holy Tradition ascribes a talent of the painter to St. Luke and credits him with having made a portrait from life of the Virgin Mary with Child. For this reason, the painters' guilds throughout Europe had the name of St. Luke.There was such a legend. When the translator of the Bible into Latin St. Jerome lived in a cloister, a lame lion came to this monastery. The monks fled in terror, but Jerome examined the sick animal's paw and removed a splinter out of it. Then, a grateful lion became his constant companion. In the artistic terms, both miniatures are designed as small easel paintings.

In the Middle Ages, there were two female images - antipodes: Eve, responsible for the Fall of Adam, ie for the original sin of all mankind, and the innocent and pure soul, the mother of Christ, Mary. In the Late Middle Ages, new trends penetrated, little by little, in these established notions. Persistent and patient love of heroines of the chivalric romances improves, heals, gives courage to the heroes and restores their lost happiness. In the 13th century, the writers-nuns Bridget of Sweden, Mechthild of Magdeburg, and others recorded their visions in their native languages. Translated by fathers - confessors into Latin, these books by women have received the status of recognized works of the Church.

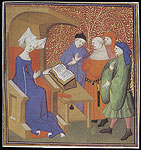

At the turn of the 14th-15th centuries, the laywoman Christine de Pizan (1365 -1430) came in French literature. Her father was a physician and astrologer at the court of the French king Carlos V, and he was able to give his daughter a good education. Christine grew up in the court environment, she had access to the royal library which was unequaled in Europe at that time. At the library, Christine familiarized herself with Roman literature, the works of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. At the age of fifteen years, she married the royal secretary. Her husband died during the plague epidemic, the father died before that. Christine was widowed and had three children to take care of. At first, she lived in poverty, but, receiving support of two royal French patrons who awarded her pensions, began to write. Christine became a professional writer. She is an author of poetry collections and 40 treatises, including essays on the role of women in family and society. Christine argued with the long-deceased Jean de Meun (1240 / 1250-1305), an author of the "Romance of the Rose", who wrote, 'Undoubtedly, ... women dishonor the name of God'. The most famous works of Christine include "The Book of the City of Ladies" (Livre de la Cité des Dames). Christine claimed that women are not inferior to men in their abilities. She saw the cause of failed marriages in specific human vices of men and women. The final work of Cristine of Pisa became "The Poem of Joan of Arc" (Le Dittie de Jeanne d’Arc).

A manuscript of the 15th century with the works of Christine of Pisa (kept in the National Library of France) is decorated with a miniature which ostensibly demonstrates respectful attitude of the contemporaries towards Cristine of Pisa. Four men stand before Christine who sits at a lectern with a book, like a teacher, and attentively listen to her reading (teaching?).It is noteworthy that in one of the NLR manuscripts, the famous theologian, Professor of the University of Paris Thomas Aquinas is depicted in the same way.

The National Library of Russia holds the mid-15th century copy with one of the works written by Christine of Pisa: “The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry”.